Against the backdrop of the ongoing Russian invasion in Ukraine, transit between Europe and Asia through the South Caucasus has been dramatically increasing as international shipping companies have started avoiding Russia for transiting cargo and seeking alternative routes due to the sanctions against the Russian railway. For instance, Maersk introduced a new rail-sea shipping service connecting Asia to Europe through the Middle Corridor via the South Caucasus and Central Asia. At the same time, Finnish company Nurminen Logistics started shipping from China to Europe via the trans-Caspian route. Shipment through the route is projected to increase six times in 2022.

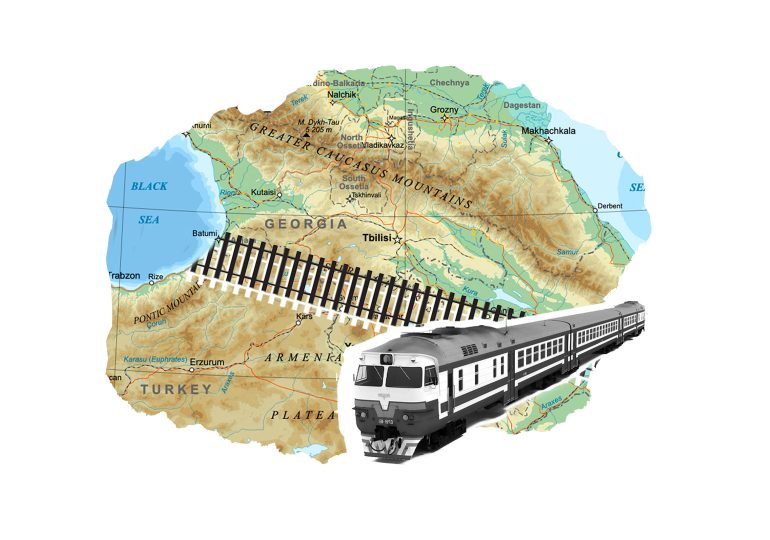

Having seen an increasing demand for transit, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Turkey decided to foster the regional transportation potential by signing an agreement on March 31. Georgia’s state railway company also started cooperating with Azerbaijani and Kazakh companies to create a new shipping route across the Black Sea between the ports of Poti, Georgia and Constanta, in Romania. An attempt to substitute the Northern Corridor with trans-Caspian routes is not new. Countries in the region, along with the European Union and Turkey, have been trying to construct transportation routes throughout the region. As a result, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and the Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA) were launched, an international transport programme involving the EU and 12 member states of the Eastern European, Caucasus and Central Asian regions.

The importance of South Caucasus and Central Asia as transit hubs was revitalised in 2013, when the President of China, Xi Jinping, launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to develop a connection with the West. The BRI is comprised of two parts: Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road, jointly distinguishing set of projects to connect China to Europe through land and sea, respectively. BRI has gradually gained global recognition and has been increasingly viewed as one of the most significant initiatives of the century. In 2017, under the framework of BRI, the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad was launched, and transportation volumes have been growing steadily since, despite pandemic-related slowdowns. However, the overall capacity of the railroad has remained limited. Similarly, the Trans-Caspian corridor involves slow and costly maritime transportation to cross first the Caspian Sea and then the Black Sea from Georgia to the ports of Romania or Bulgaria and utilises an underdeveloped rail route through Turkey.

It is noteworthy that a decade-long major modernisation of the Georgian railway is expected to be completed this year, which will double its freight transportation capacity. However, there are concerns that the overall regional infrastructure in the South Caucasus is underdeveloped to respond to the surging transit demand. One of the main concerns has been the cancellation of the Anaklia deep-sea port, which had been expected to play a crucial role in intercontinental transit. Even though the Georgian government still claims that building the port remains a priority, there has not yet been a new procurement for companies to take over the project. The lack of a deep-water port decreases the prospects of the Trans-Caspian corridor becoming the main transit route between Europe and Asia.

In the meantime, Azerbaijan has tried to utilise the increasing interest in the Middle Corridor. On the 30th anniversary of bilateral relations between Azerbaijan and China, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, in his letter to Xi Jinping, emphasised cooperation in transportation, underlining the importance of infrastructure projects in transportation and transit for the cooperation between the two countries. The Azerbaijani government has sought to expand the capacity of the Port of Baku, given the rising demand occasioned by Russia’s isolation from the key project of the industrial park at Azerbaijan’s new Port of Baku. Additionally. Recently, a Parliamentary delegation from Kazakhstan visited Azerbaijan to discuss opportunities of redirecting transit away from Russia to the South Caucasus.

Despite these developments, several challenges remain to Chinese transit through Azerbaijan. Firstly, it is not a key part of China’s land-based trade and energy network. At the governmental level, China has failed to close several key financial agreements that will boost economic ties with Azerbaijan. There are currently no agreements on currency swaps, industrial transfer, or free trade between the two countries, though China has concluded such agreements with Georgia and Armenia. On top of that, Azerbaijan has not shown any great enthusiasm for upgrading its old and slow railway infrastructure, which is needed to accommodate Chinese cargo arriving from Kazakhstan via the Caspian Sea.