Salt used to be a vital resource that was brought to Georgia from various ancient empires. Colchians would exchange it for lumber, linen and slaves. The Laz even started a conflict with Byzantium over the price of salt. The following article explores the history of the Black Sea salt trade route.

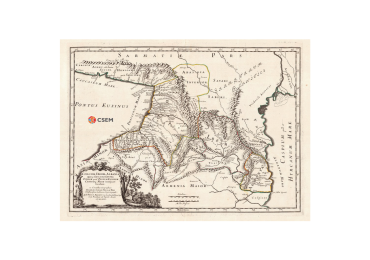

Greek colonists first established the Black Sea salt trade in the classical era. Milesian Greeks founded the Panticapaeum colony on the shores of Crimea in the VII-VI century BC and began trading with neighboring states. Colchians sold lumber, linen and slaves and, in return, sought resources they could not find in their territory, including salt. After the fracture of the Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) remained in control of the Black Sea region and continued to actively trade with the kingdom of Lazica that had been formed in western Georgia. The VI century historian Procopius of Caesarea highlighted the importance of the salt trade to the Laz. In 535, the Byzantines built the fortified city of Petra in Lazica and used it to start monopolizing the economy. All commercial goods, including salt, would arrive in Petra, where the Greeks would purchase them and resell them to the Laz at a substantially higher price. This policy led to a conflict between Byzantium and Lazica, with the latter temporarily allying themselves with the Sasanian Empire.

Since ancient times, salt has been a vital resource that played an essential role in the trade relations of great civilizations. Egypt, Rome and Greek city-states had a state monopoly on salt trade. Sea salt was obtained from the Dead Sea and the Adriatic Sea, while rock salt was found in the Carpathian Mountains and the Pyrenees. Salt deposits expanded and became more important over the centuries. Homer and Plato called it a divine substance fit for the gods. Everyone who came across salt immediately understood the value of this mineral and tried to obtain it.

The importance of salt created the need for so-called salt routes that allowed this product to be imported to regions where salt was in short supply. For example, the 246 km long Via Salaria stretched from Rome to the Adriatic Sea. Although the Tyrrhenian Sea was much closer to Rome, it was nowhere near as salty as the Adriatic. According to a legend, the Romans used salt to pay their soldiers, hence the term salary. Based on a different version of the story, the soldiers received additional money to buy salt. In truth, most scholars have rejected both versions due to lack of evidence.

In medieval Germany, a 100 km ‘salt road’ ran from Lübeck in Schleswig-Holstein to Lüneburg in Lower Saxony. Lüneburg was famous for its salt deposits. From there, salt would be taken to Lübeck and distributed across the Baltic Sea coastline. The Lüneburg salt was one of the sources of wealth and power of the Hanseatic League. In XV-century Bosnia, the Via Narenta was used to transport salt between Dubrovnik and Podvisoki. Similar routes operated all over Europe. The vast rock salt reserves were important in allowing the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to establish itself as a powerful empire. Polish salt was exported to all parts of Europe through the cities of the Hanseatic League. In XII-century Bavaria, Duke Henry the Lion afforded Munich city status in order to control the salt trade. The so-called salt taxes were a significant source of income for countries through which the salt trade routes passed.

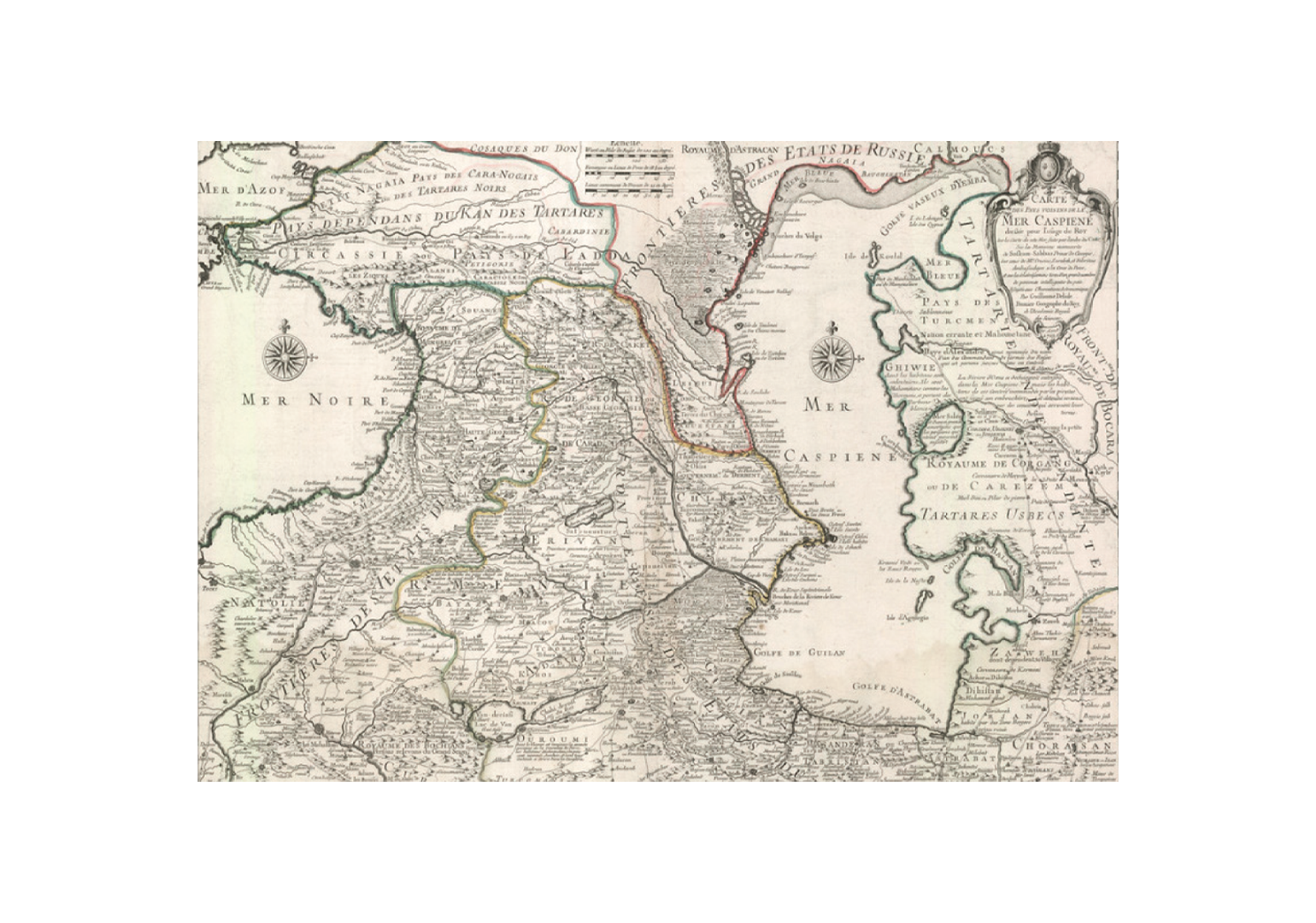

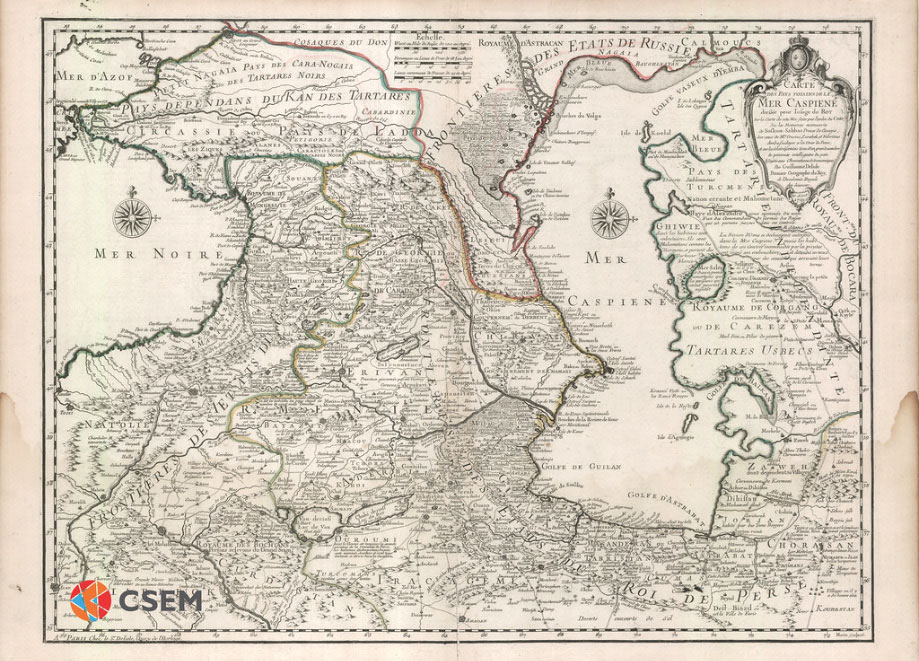

Greek colonists first established the Black Sea salt trade in the classical era. Milesian Greeks founded the Panticapaeum colony on the shores of Crimea in the VII-VI century BC, followed by Theodosia, Kimmerikon, Tyritake and Myrmekion. Samos Greeks built the city of Nymphaion, while Greeks from Heraclea in Asia Minor built Chersonesus. Among other resources, the Greeks began mining salt in this region. Syvash Bay contains 180 grams of salt per liter of water, which is ten times the salinity of the Black Sea. When water recedes in the summer, the salt remains on the surface and is easy to collect. The Greeks transported the salt via land routes to Chersonesus and Panticapaeum, where it was loaded onto commercial ships. Naturally, the Greek cities in Crimea had a close relationship with the other Greek colonies on the Black Sea’s eastern, western and southern shores, including Phasis, Dioscurias, Pityus and Gyenos in modern Georgia.

According to the Greek geographer Strabo, the salt transported to Dioscurias was bought by the Colchians and other peoples from across the mountainous regions of the Caucasus. Colchians pursued fishing but did not have enough salt to preserve their catch. Fish was mainly salted in Crimea and the western seaboard of the Black Sea. From there, it was supplied to the cities of the Black Sea region and the Greek polises and settlements on the Marmara and Aegean coasts via the Bosphorus and Dardanelles. The Aegean Sea was not particularly rich in fish, so the supply of salted fish from the Black Sea colonies would have been crucial to the Greek city-states on the Balkan Peninsula.

The Black Sea salt trade continued without disruption through the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The eastern hellenophone space remained virtually untouched for centuries, while the Mediterranean Sea became Mare Nostrum (“our sea”) to the Romans. Rome aimed to control all key locations on the Black Sea coast. The western and southern shores were fully incorporated into the Roman Empire, and several strongholds were established in Crimea under Vespasian (69-79 AD). As for the eastern seaboard, although Colchis was not an imperial province, the coastline with its strategic strongholds was also controlled by Rome. Thus, the Black Sea trade would almost certainly have been dominated by the Romans.

Salt trade during the Middle Ages continued to be associated with the salt production centers of the Black Sea region. Genoese colonists appeared in the XIII century and established their base in Kaffa (Theodosia), which they purchased from the Golden Horde. The other Italian trading powerhouse, in the shape of Venice, also became involved in the salt trade.

Salt trade played a crucial role in the economies of Genoa, Venice, and the Mediterranean region as a whole. In 1260, Genoa imported salt from Provence, Ibiza, Sardinia, and Alexandria. It also had exclusive rights to import salt to the French cities of Toulon and Hiers. Crimea was added to this network in the 1270s. The Genoese actively began obtaining salt from the “putrid sea” of Syvash, from where it was transported to Kaffa or other nearby ports to be loaded onto ships. Salt could also be obtained from hundreds of Crimean lakes.

Records of Genoese activity in the Black Sea salt trade first appear in a 1278 Greek report, according to which the merchant Corrado di Reinaldo di Noli had his salt cargo inspected in Constantinople. Based on an Italian source, Genoa exported 390 tons of salt to Trebizond, 565 tons to Sinop and 112 tons to Cerasus. Presumably, more was exported to Constantinople. Armenians, Alans and Tatars also participated in the salt trade. We find many names of Turkic origin in the accounts of the salt trade, which means that local Crimeans were actively involved in the extraction of this precious resource and the trade with Italian resellers.

In 1317, regulations came into force banning the Genoese from selling salt in Constantinople. They could only export the product to Europe. Trade expanded even more in the XV century, with Trebizond becoming one of the leading commercial centers. Salt was relatively cheap, but the cost of transportation tripled its price. Consequently, the Genoese sold salt at a high price in Greek cities to cover the cost of transportation and make a profit.

The Genoese shipped some of their Crimean salt to Europe, but like fish, the main destinations were the Black Sea countries. In Trebizond, they bought goods such as silk and spice, with the proceeds from expensively sold salt.

In the XIII-XV centuries, the Genoese exported wax, linen, silk, fur, wood, leather, grain and even ghomi from Georgia. In return, they imported European handicrafts and woolen fabrics. Their Crimean colony sent enormous quantities of salt and fish from Kaffa. According to the XV-century Venetian diplomat, merchant and traveler Giosafat Barbaro, “Samegrelo is mostly rocky and barren. Apart from ghomi, they do not produce any other food. They bring salt from Kaffa (Crimea) and make linen from hemp and nettle, which is of low quality.” Another contemporary Venetian traveler, Ambrogio Contarini, said, “Little bread gets made in Samegrelo. They also make wine but of low quality. The main food is ghomi. These people’s lives would be even worse if they did not bring wine and salted fish from Trebizond and salt from Kaffa.”

As in antiquity, there was commercial activity on the west coast of Georgia throughout the Middle Ages. Imported salted fish would have been vital to areas that lacked foodstuff. Salt was also a necessity for seasoning and preserving food.

In the XV century, the Black Sea became an Ottoman lake. The Crimean Khanate was an Ottoman vassal. The Ottomans received slaves, grain, meat and salt from Crimea. The Ottoman Empire took over the monopoly of the salt trade. Western Georgia’s foreign trade was also subordinated to Ottoman interests at that time. Foreign markets were closed to local merchants. The supply of basic goods for Western Georgia depended on the will of the Ottoman Empire. By this time, there was often a shortage of salt. Ottoman tribute and feudal and state taxes were a heavy burden for the population, while salt was quite expensive. There are known cases of Georgian kings and princes paying tribute on the condition that the Ottomans would bring salt and other necessities to Georgia. This again points to the vital importance of the Black Sea trade for Transcaucasia, especially the need for salt, which remained throughout the centuries.

Following the conquest of the Crimean Khanate by the Russian Empire in 1783, control of the salt deposits changed hands once again. The Russians continued to extract salt from Syvash and export it by sea and land to other imperial provinces (including Georgia) and beyond. From the XIX century, salt and other basic items became more widely available. At the same time, many new products were introduced, including corn, beans, potatoes, sunflowers, pumpkins, new varieties of wheat, cocoa, tomatoes, and more.