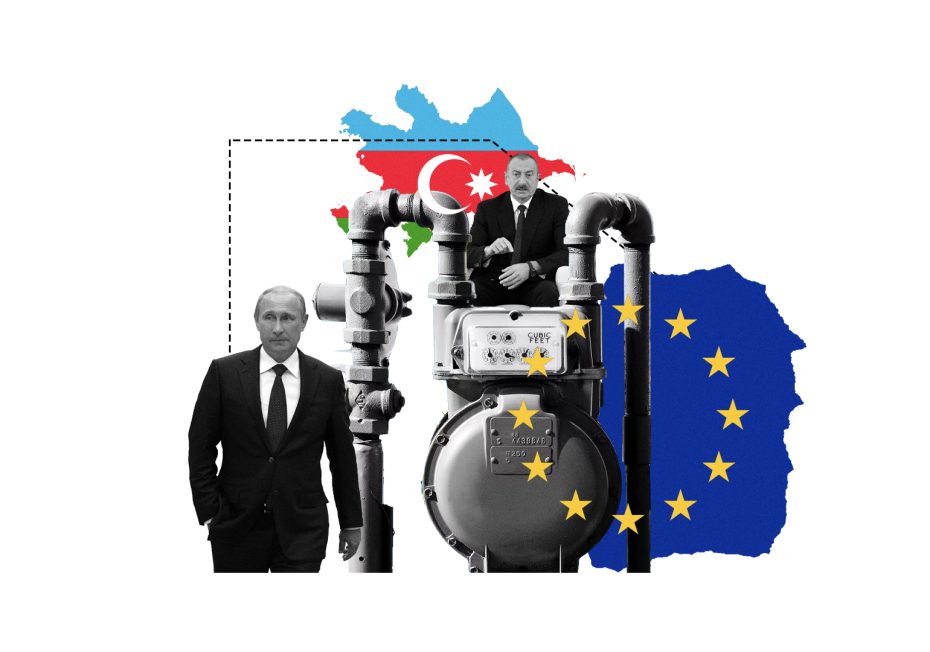

On November 18, Russian state gas company Gazprom made a statement that it had started supplying gas to Azerbaijan and would export up to a billion cubic meters. By receiving gas from Russia, Baku is trying to maintain supplies to its domestic gas customers as well as the importers of Azerbaijani gas, such as Georgia, Turkey and the EU. According to the Memorandum of Understanding between Azerbaijan and the EU concluded on July 18, gas exports to the EU will be increased up to 12 billion cubic meters by the end of 2022 and exports will be doubled through the Southern Gas Corridor to 20 billion cubic meters a year by 2027 – the maximum that the existing pipeline network can carry. The increase in the energy volume is intended to help Brussels to diversify its energy imports, namely to find alternatives to Russian gas, which has been cut by Moscow in retaliation for EU sanctions imposed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While the gas purchases from Russia can help Baku meet its ever-increasing domestic and foreign demand, it has raised serious concerns over the EU-Azerbaijani memorandum on boosting Azerbaijani energy exports to the EU, which aims to decrease the EU’s dependence on Russian energy.

Now, Azerbaijan has set to import gas from Russia this winter, which suggests that it intends to use Russian gas to meet the demand of its domestic market and free up gas to meet its commitment to Brussels. While the sanctions imposed by the EU against Russia do not apply to Azerbaijan, which remains free to import as much Russian gas as it wants, the new deal between Baku and Moscow contravenes the political intention of the July energy agreement, which was agreed upon specifically to boost the volumes of Azerbaijan gas flowing to Europe so as to help the EU reduce its dependence on Russian gas. Facilitating imports from Azerbaijan to the EU with help from Russia undermines Brussels’s effort to diversify its energy market both in the short and long terms as Moscow can any time cut off its gas exports to Azerbaijan.

For the time being, Azerbaijan is not capable of producing and providing 12 billion cubic meters of energy to the EU. The country has limited scope for increased production and its gas export to the EU will completely cling to Russian “emergency aid.” In the meantime, there is a lack of investment in developing new energy fields, which in short term could be solved by importing gas from Turkmenistan, under the three-way gas swap agreement concluded between Baku and Tehran in December 2021. Under this deal, Turkmenistan pledged to supply between 1.5 and 2 billion cubic meters of gas a year to north-eastern Iran and a similar amount of gas would be supplied from north-western Iran to Azerbaijan. However, the current status of the deal remains unclear. Azerbaijan’s unexpected need to import Russian gas raises the suspicion that that agreement may have been undermined by unstable relations between Baku and Tehran. Due to these issues, it is hard to blame Azerbaijan for putting its own economic interests ahead and the EU has not yet made large-scale investments in the development of new gas fields in Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan’s lack of capacity to quickly solve the European energy issue pertains to a lack of production due to underdeveloped fields and the insufficient capacity of the existing pipelines. Azerbaijan possesses several gas fields in the Caspian Sea, the majority of which are currently either under development or awaiting the necessary investment. More gas production, coupled with higher demand from Europe, would provide a stronger investment case for the expansion of the current TAP and TANAP pipelines as well. The EU, along with the US, whose presence has been growing in the region, especially since the recent clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan, could jointly invest in infrastructure and the development of the existing pipelines. The inclusion of Armenia in the energy projects would also reinforce reconciliation efforts from both sides.

Importing Russian gas indeed puts some part of the EU’s energy diversification under threat. Nevertheless, as it is still too early to claim that Azerbaijan will be able to significantly boost its gas exports to Europe in the short term due to the limited amount of gas, Moscow will not be able to exercise any significant leverage over the EU. Azerbaijan can only provide a mere 8 per cent of Russia’s previous gas export volume by the winter of this year, and around 14 per cent by 2027, as envisioned in the EU-Azerbaijan energy agreement. Hence, it might take up to a decade for Azerbaijan to become sufficiently capacitated to export the volume of natural energy needed to fully meet the EU’s energy demand and become a game-changing alternative for Russian energy in Europe. In the meantime, the EU should actively push new investments for gas production development in Azerbaijan.