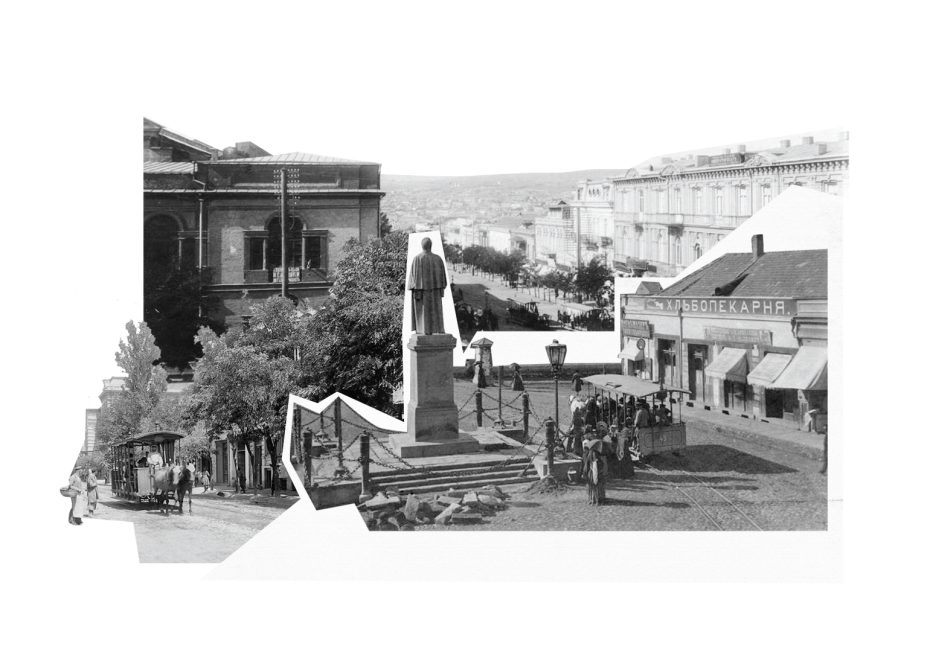

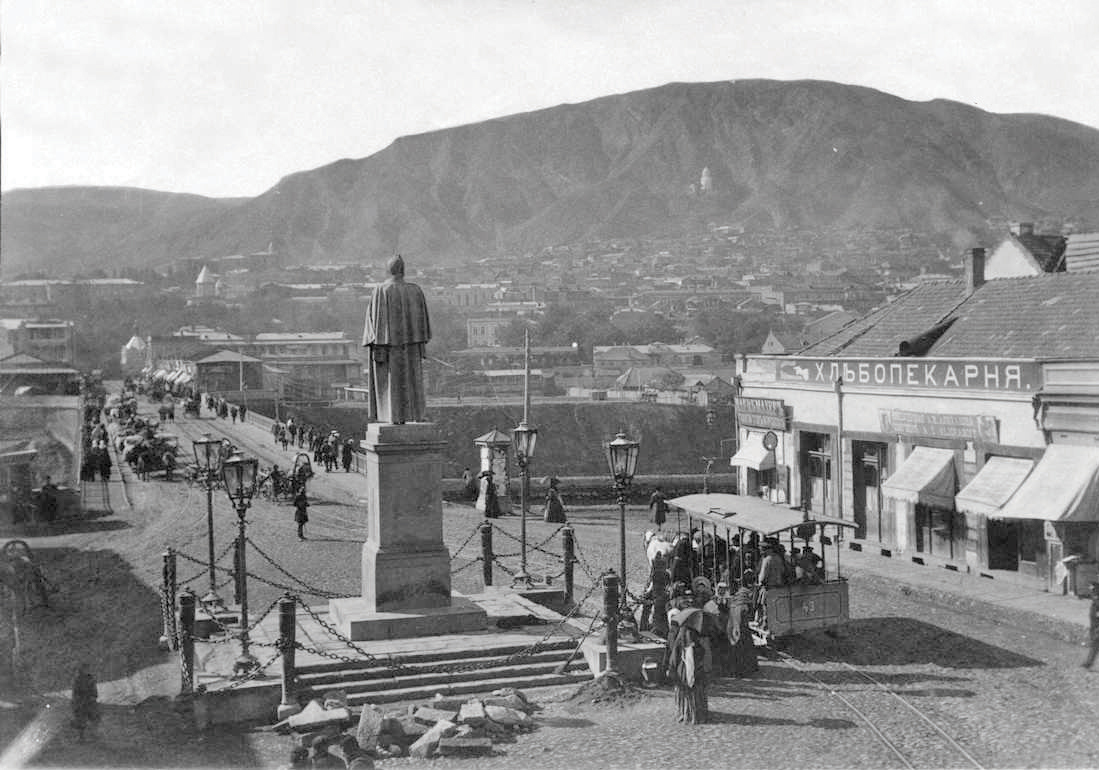

In 1883, something significant happened in the history of Old Tbilisi. A new form of public transport was launched in the shape of the “Konka,” or horse-drawn railway. Prior to that, the whole town was talking about the proud horsemen of Tiflis, their speed and self-control: “Nowhere can you find such spoiled and proud horsemen as in our city.” The “Konka” became the main topic of conversation across the city.

“The afternoon is upon us. Sunny spring is calling people outside, and the streets are full of pedestrians. People are gathered in large numbers in front of the Vorontsov Monument and on the corner of Mikheil Street. Several kintos are stood together. One of them, with a worn dress and Muscovite peaked cap, resembles a bankrupt petty trader. Fresh out of the bakery and covered in flour, a man from Racha is preoccupied with his pipe, paying little attention to those around him. Two horse-drawn cab drivers have stopped and are staring enviously at something. Everyone seems to be looking in one direction, expecting to see something amazing. Kids start shouting: “They’re coming! They’re coming!” And indeed, here they are… Three horse-drawn carriages coming down the road…” – David Kezeli (Aragveli), ‘Scene on the Horse-Drawn Railway

Let us start by pointing out that the horse-drawn railway was the first form of public transport that made regular journeys across the city. The passenger carriage, which was pulled by horses, was open and could accommodate two dozen passengers. However, before discussing the advantages and disadvantages of this form of public transport, let’s review the news that preceded the launch of the “Konka” in Tiflis.

In early 1881, the “Kavkaz” newspaper reported that “two rich individuals” had arrived in Tiflis intending to construct a horse-drawn railway. On its part, the city’s administration was far from idle. “A project was drawn up to lay horse-drawn railway tracks from the Central Station to several major streets.” Additionally, a similar project was presented by a certain Dzhevetsky. According to the rumors at the time, the construction of the horse-drawn railway was going to be entrusted to Dzhevetsky’s company.

“The parties who have undertaken to build a horse-drawn railway in Tbilisi have prepared all the necessary road plans and drawings, which they will present to the city government in the coming days. Upon obtaining approval, they will immediately start implementing the work, and by the spring, they will be able to finish the Mushtaidi – Alexander Garden section,” the “Kavkaz” newspaper wrote in the summer of 1881.

However, things went quiet in the subsequent months. Then the word spread that “the government and the city administration could not strike an agreement with the man who had presented the railway project.” To the joy of the people of Tiflis, a year later, it was revealed that “the construction of the horse-drawn railway was already underway.”

“Our city will soon be adorned by a horse-drawn railway, which they are working hard to complete. We can expect the railway to be completed any day now. A main station with stables and carriages is being built [in Kukia]; the rails and carriages are said to be on the way and should arrive soon. Assembling the rail lines themselves does not require much time.”

“The expansion of Kukia Bridge is not an obstacle. This matter has been entrusted to a separate commission, which will hopefully ensure that the rails used for the horse-drawn railroad do not impede the movement of people and horse-drawn cabs down both sides of the bridge.”

“The whole Tiflisian community and I think even the Kartli-Imereti region are impatiently waiting for the completion of this railroad to avoid the shameless profiteering of horse-drawn cab drivers.”

Do not think that horse-drawn cab drivers have been mentioned randomly. Firstly, public transport would become more affordable compared to the carriage services, and secondly, Tbilisi was a city where “you had to yell at least ten times for a horse-drawn cab driver parked on the street to look your way and reply to you.”

The first two lines of Tbilisi’s horse-drawn railway led to the central train station and Mushtaidi. As years passed, “Konka” tracks covered most of the city’s streets. “The horse-drawn railway line between the Vorontsov monument and the train station will be fully completed and operational this month,” the “Droeba” newspaper wrote on 1 January 1883.

As mentioned earlier, the Tiflis horse-drawn railway was a topic of constant discussion even before its opening. Moreover, there was an awkward debate on this form of public transport in the City Council, with one of the members regarding the presence of second-class carriages as a “definite necessity to separate the upper and lower classes of society.”

In response to this proposal, the counselor received a delicate remark from his colleague: “It is not only inconvenient but also unfair whilst the wearers of chokha and sertuk are still alive.”

Despite such pointless disputes, the special commission of city officials was also getting work done. They personally inspected the horse-drawn railway before its opening:

“The line between the central train station and Kukia Bridge is ready and will open in a couple of days. The carriages will hold twenty people. The footrests are so low that even a child will be able to get on and off freely.”

“We liked the road conditions – only in a couple of places did we feel unevenness and a noticeable vibration of the carriages. This is only because the road is not well compacted yet.”

“Closed carriages are also being prepared for autumn and winter. The horses are excellent and well-trained. There are thirty carriages in total and one hundred and twenty horses for whom a large building will be erected on the top of Mushtaidi. Workshops, where carriages will be built, are nearby,” we read in the 25 February issue of “Droeba.”

The next day, on 26 February 1883, the “Konka” was finally launched. The head of the city administration notified the regional governors of this joyful news and received congratulatory telegrams in response:

“Delighted to hear about the opening of a horse-drawn railway in Tiflis. I congratulate the locals. Thank you for informing me. Mikhail.”

“I heartily rejoiced at the opening of the horse-drawn railroad, which will make transportation easier for residents.” – A. Dondukov-Korsakov

Congratulations aside, the whole city was rejoicing. “Everyone was looking with gratitude at this railroad, these pretty carriages.” After the opening of the horse-drawn railway, many people took the journey from Kukia Bridge to the Central Station, especially since it was cheaper to travel by “Konka.” They said, “You can go wherever you want – up and down, back and forth, and you can get around at least half the city for the price of one abazi.”

However, this back-and-forth travel soon became a problem. Specifically, a columnist of “Droeba” criticized the section of the Tiflisians who failed to understand that the horse-drawn railway was not launched to give idle people sightseeing rides but to connect remote parts of the city and provide transportation:

“The townspeople have misunderstood the purpose of this service. They take their whole family, occupy the entire carriage, and will not get out until they complete five or six journeys. So, those who really need to get to Mushtaidi or another destination along the route often cannot find a place to sit.

“A man must have a whimsical spirit not to get bored of one journey and repeat it four or five times! In addition, on beautiful days, some people feel like going for a walk in Mushtaidi, but due to the fear of losing their belongings, they don’t get off and instead go back…”

From today’s point of view, this may raise an eyebrow, but it seems to have been a serious problem for the people of Tiflis, who wrote complaint after complaint about the overcrowding of the “Konka” and offered a solution to the people responsible for the operation of the horse-drawn railway:

“They built a horse-drawn railway in Tiflis, and the public didn’t gain much from it. Women and children wait for hours for the carriage to come, but as soon as it arrives, they are pushed back by the kintos and other wealthier people. And so, they wait for the arrival of the second and third carriages with the same result.”

“Would it be difficult for the railway administration to introduce rules similar to those they use abroad? It turns out that horse-drawn railroads abroad also have stations. People buy a ticket and are given a number, which they use to queue for a place in the carriage. Through these rules, women, children, and other weaker individuals would be spared the experience of jolts, torn clothes, and broken umbrellas, and we would all be grateful to the administration of the horse-drawn railway.”

Even without this, the horse-drawn railway tracks in Tiflis were not exactly strewn with roses – problem after problem appeared. The first big challenge was the narrowness of the streets of Tiflis. In the streets where the “Konka” tracks passed, there were “a lot of people walking around.” Not infrequently, the carriages would derail, so special care was needed to avoid accidents.

Newspaper reporters also openly spoke about the organic issues affecting the railway and implored the powers that be to find a solution:

“The main drawback of this railroad is that the tracks are very high above the street surface. Thus, when the carriage travels along this stretch of road, the coachman cannot easily make a turn because the wheels of the carriages stick to the tracks and follow them for several fathoms. It is impossible for him to make a sudden turn, and when the wheel jumps out of the tracks, passengers get thrown around. Only the other day, a young man fell off, barely escaping death. Such cases, as they say, are widespread. In addition, the height of these rails means that in a month or two, the city’s horses will be left with no legs.”

“The second disadvantage is that it has become very difficult to move around the narrow streets through which the “Konka” passes. Sometimes a carriage derails; at other times, there are too many carriages passing through or too many pedestrians. In these locations, an accident may happen at any second. At the end of Mikhailov Street, the tracks are so close to the sidewalk that if a person were to trip or be pushed by someone, they would end up under the wheels of the “Konka.” Unfortunately, the sidewalk in this place is very narrow. The same bad conditions will affect the “Konka” when it starts operating near the Russian Bazaar, Palace Road, etc.”

“These are the main organic drawbacks of the city’s railway. Some shortcomings are caused by the administration. For example, there are very few carriages in the morning until twelve o’clock, so the service cannot meet people’s needs.”

“It is vitally important to at least address the issues that can be corrected. Otherwise, a tragedy is just around the corner…”

Naturally, accidents did happen, and in no small number.

“On Sunday evening, the “Konka” hit a horsedrawn cab on Mikhail Street and tore it in half”; “Another disaster on the horse-drawn railroad: this time, the victim was a railway conductor whose body was cut into several pieces”; “On Sunday, a high school student was killed by a horse-drawn carriage traveling along its route”; “In so short a time, no one has so excelled in killing and maiming men than as our horse-drawn railway.”

Along with all the other troubles, residents complained that the horse-drawn railway drivers continued the city’s infamous tradition of racing down the tracks as if there were absolutely no obstacles in their way.”

The consensus among the railway’s critics was that most of the problems stemmed from the narrowness of the city’s streets:

“It would be foolish to hand over all our streets to this railway project. The streets of Tiflis are generally so narrow that one must even be careful when navigating Galavani Avenue, let alone crossing the Kukia Bridge to the bazaar… This bridge has always had so many people on either side that it was already sometimes difficult to move, and now even this bridge has been lost to horses, as tracks go in both directions! Effectively, the city has handed this bridge over to the horse-drawn railway company. Even a blind person would understand that if carriages start to cross this bridge in both directions, the horses will find it difficult to pass, and the pedestrians will also be in great distress…”

Nevertheless, through good and bad times, despite the “barking” of critics and well-wishers alike, the “Konka” continued to operate, and the network of tracks of the city’s first form of regular public transport continued to expand.

And so, it continued until, in 1904, the horsedrawn “Konka” was replaced by the “Conca,” an electric tram.16

ძველი თბილისის მკლევარი.