The 21st century has begun with beyond-expected leaps in development in a plurality of spheres. Humanity has once again showed, both, its potential and limitless creativity. However, there are still countless problems to solve, starting from inequality and discrimination and ending with excess power centralization. Regrettably, all of this comes with horrific consequences and blameless people are the ones who pay the price.

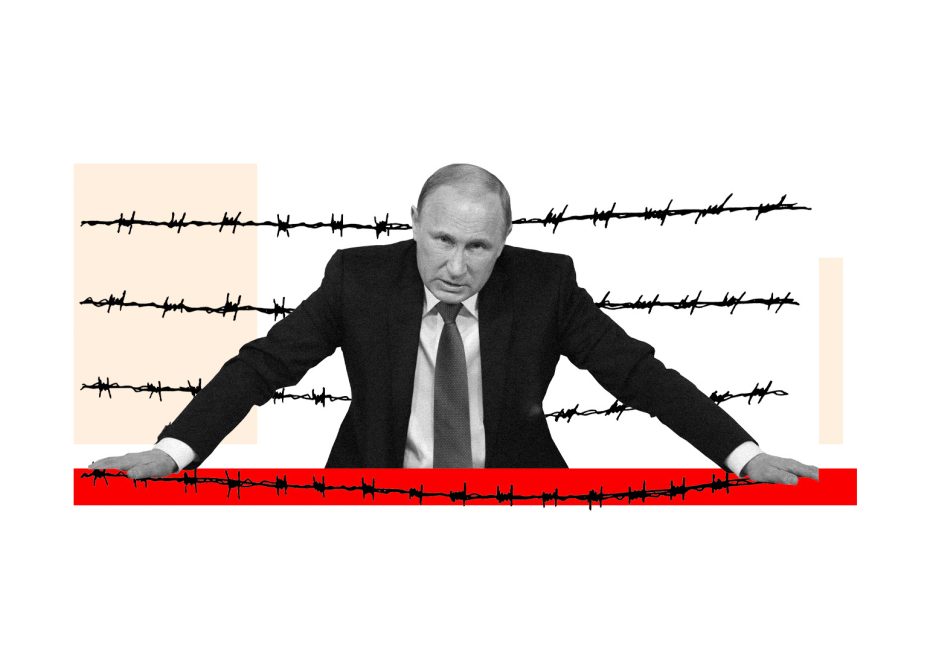

Since February 24 2022, a huge conflict raging between Russia and Ukraine has dominated Ukrainian territory, counting more than 23000 casualties. At this point, Russia, undoubtedly, not only continues the occupation of Ukrainian territory, but also uses its momentum via propaganda and false information to hide behind the name of “Liberator”.

Unfortunately, this is not the first time Russia has considered this approach to justify its expansionist steps and raise confusion in global societies.

GEORGIA AND UKRAINE: A MERE COINCIDENCE? WE THINK NOT!

A prime example can be the 2008 Russia-Georgian war and, when analyzing the officially posted Presidential decrees regarding the conflict, it must be more than just a coincidence that the structure of the decrees matches perfectly.

Firstly, Moscow recognized the independence of its puppet quasistates “considering the will” of natives of both Ukraine and Georgia. In other words, rather than explicitly stating it has engaged in a war with these countries, Russia has consistently referred to the occupied territories as independent states (first paragraphs of the decrees) and regarded the natives’ defense as its main mission. However, with over 1100 civilian casualties (out of which 99 are children) in Ukraine and 224 in Georgia, data proves otherwise.

Secondly, national propaganda has also created a false perception within Russian communities in order to galvanize discriminatory behaviors, with the majority of Russians being in favour of the President’s decisions. What is more, there still is a huge influence of Putin’s power over Ukraine and Georgia. Both are post-soviet countries with approximately 40% and 30% of the population, respectively, being Russian speakers, who can be easily influenced by misinformation. The latter has caused doubts and conflicts in societies of the occupied countries, playing in Russia’s autarchic hands, even when the majority of people in both countries have a precise idea of who is the real aggressor.

Thirdly, Russia perceived the expansion of NATO borders as an extremely dangerous signal of possible attacks from the latter’s territory and seemingly demanded neutrality from both countries’ political elite. With two out of three aspiring NATO members being the direct neighbors of Russia, President Vladimir Putin has frequently mentioned, what he perceives as, systematic risks and problems associated with such expansion. International politicians have been debating whether neutrality will serve as a mere guarantee for peace. Georgia’s history gives a clear suggestion of why the latter argument is not legitimate; in 1993, the first territorial conflict arose between Russia and Georgia. Yeltsin’s forces helped native Abkhaz separatists capture Sukhumi and gain control over the whole region. After displacing 300,000 civilians from the region and significant human rights violations, largescale ethnic cleansing against Georgian population remaining in Abkhazia caused terrible devastation from an economic, cultural, and political perspective.

Most importantly, all of this happened before Georgia became an aspiring NATO member. Georgian people have consistently demanded NATO membership (and even inserted aspiration will into their constitution) since this first instance of occupation to gain protection against Russian occupying forces.

POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION: WILL A SHORT-TERM RESPONSE BE ENOUGH?

The wars between Russia and Georgia as well as Ukraine have led to distinct political consequences by and for the European Union (EU). While in 2008, the Union was impeded by its own internal division over a united standpoint towards Russia, it has impressively demonstrated its unity during the ongoing crisis in Ukraine. While France, Germany and Italy advocated for a moderate response to the Georgian war, not least because of their energy dependence, central and eastern European countries – particularly Poland, the Czech Republic and the Baltic states – have seen their own security at risk and stood up in favor of more determination against Russia. It was mainly due to former French president Nicolas Sarkozy’s initiative that a six-point EU-peace plan could have been agreed upon by all parties, resulting in the war’s termination. Sarkozy’s visit to Georgia and Russia was the EU’s only short-term response apart from public condemnation of the crisis.

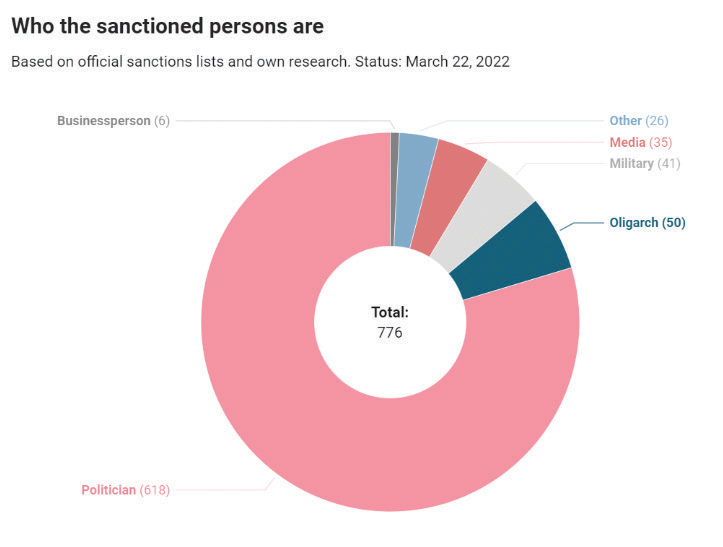

In contrast, the contemporary war has been characterized by unprecedented European unity and the rise of the EU as a geopolitical powerful actor. A prime expression of this is the fast and comprehensive sanctions against Russia which efficiently came into force two weeks before the attack. What followed on February 24 – the day of the invasion – was a bundle of sanctions in the fields of finance, energy and related-transportation, dual-use goods, export controls, visa policies and measures against individual Russian oligarchs. In further steps, the wealth of Vladimir Putin as well as Sergey Lawrow was frozen, transactions with the Russian central bank (Bank Rossii) as well as flights over the EU airspace prohibited. On March 2, the EU excluded seven Russian Banks from the international SWIFT system. Even “taboos’’ such as the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline are currently under discussion, despite potential severe negative consequences for Europe itself.

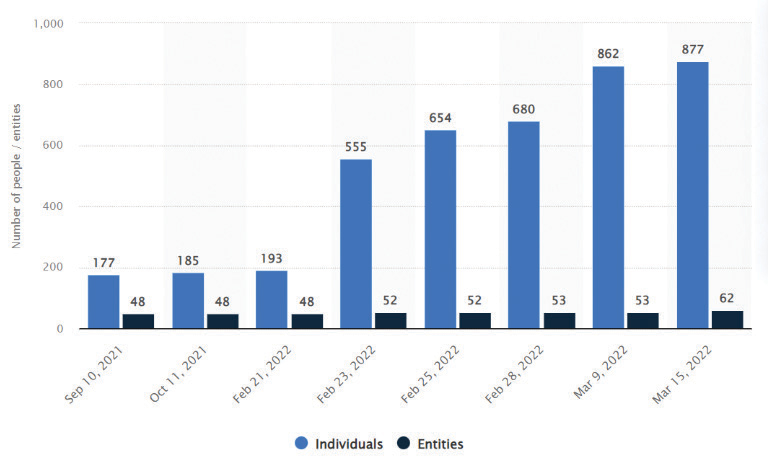

Cumulative number of European Union sanctions against individuals and entities related to the Russia-Ukraine war from September 2021 to March 2022

Once again, the Union had to realize its dependency on Russian energy and the vulnerability that comes with it which must not be considered a sous entendu. While the war in Georgia already caused an outcry for a more diversified energy portfolio, the current situation shows that too little has been done. Regarding the war against Ukraine, the efforts are more than credible, and the EU has announced to cut its gas dependency on Russia by two-thirds this year, while committing to ending it entirely by 2030. Negotiations between Germany’s Minister of Economics Robert Habeck and Qatar as well as the United Arab Emirates concerning energy supplies are exemplary of this commitment.

While the cut of energy dependency is one of the three major policy implications as a consequence of the war in Ukraine, the crisis has also urged European member states to take their defense much more seriously as well as to cope with large migration flows. At Versailles (March 11,12), European leaders agreed to raise “substantially” their spending for defense and Germany – as one of the leading EU members – has pledged to meet NATO’s expenditure target of 2 per cent of its GDP on defense, and announcing a 100 Euro billion ad-hoc defense fund.

At the same time, huge migration flows are reaching the EU. An estimated 3,6 Million people have left Ukraine and 6,5 Million have been internally displaced. As of March 23, Poland and Romania have given refuge to more than 2,7 Million refugees and shown the EU’s prominent willingness to help.

THE SUBSEQUENT ECONOMIC CHALLENGES: A WORLD PERSPECTIVE

Stagflation has been intimidating again the European economic state of affairs recently, as it did in the 70s in the post-OPEC crisis scenario. As an obvious outcome of the pandemic, this threat has been peculiarly reinforced by the conflict in Ukraine. Inflation has touched the unbelievable 5.7% rate, due to the massive impact of increasing energy prices (equal to 31.7%). While the Fed has already announced a restrictive monetary policy as an inflation antidote, the ECB has highlighted its willingness to decrease the purchase of long-term government bonds if the expectations are not to be adapted toward the 2% macroeconomic goal.

Furthermore, in the oil sector, Moscow and Kiev cover 2% of the global market, i.e. supply.

However, a large part of both countries’ GDP is dependent on the trade of raw materials, which are not to be considered easily substitutable; consequently, the conflict is accelerating this inflationary trend specifically in energy prices. Due to remarkable dissimilarities in the type of energy sources demanded, European leaders have not been able to find any agreement on a potential price cap yet: Southern European countries heavily depend on Russian gas, i.e. a price cap would be beneficial, while Germany and the Netherlands would rather prioritize a shift to renewable and sustainable energy sources.

Concerning the previously-mentioned Nord Stream 2, Victoria Nuland, US Under Secretary of State for Political affairs stated: “I think Nord Stream 2 is now dead. I don’t think it will ever be revived”. The pipeline has been blocked by German political authorities immediately after the Ukrainian invasion, causing damages not only to Gazprom, but also to several European corporations. Indeed, the pipeline is the result of an agreement of 9.5 billion euros among Nord Stream 2 Ag (under Gazprom), the German Uniper and Wintershall, the French company Engie, the Austrian company Omv and the EnglishDutch Royal Dutch Shell. While Wintershall has considered a proposal for reimbursement, Omv, Uniper and Engie believe that the pipeline will be reopened in case of a conflict’s diplomatic solution.

In a nutshell, the MEP Michael Scannell explicitly declared that the Ukrainian invasion will clearly impact traders’ rush to find alternative markets for a wide range of commodities’ investments (February 28). The countries that Ukraine exports most of its maize to are China and the EU members, which clearly have the structural capacity to import from other world regions. Effects might turn catastrophic in the African continent, being heavily dependent on maize and food sources’ imports.

THE ONLY CREDIBLE MEDIATOR: TURKEY AND THE MONTREUX CONVENTION

This world scenario is destined to become a common ground for all world countries, but the neighboring countries will certainly be affected more.

As every country is picking sides in the war, leaders of the countries in the region are presented with a strategic dilemma. The governments that have been trying to balance their relationships with both the West and Russia are now pressured to pick sides.

A priori due to its location, Turkey is certainly one of the most important actors in the region. Being a NATO member while trading essential goods with both Ukraine and Russia, nowadays Turkey is certainly walking a fine line. Unlike many NATO member states, it has not been applying sanctions and the Turkish airspace is not a forbidden fly zone for Russian aircrafts. With an already vulnerable economy, fighting high rates of inflation (officially 54.4%, in reality, citizens perceive it even at a higher rate), Turkey cannot afford to damage its bilateral relations, since Russia is the key source of imports and the main source of revenues from tourism. 16.7% of all imports in 2021 were from Russia, consisting of essential goods, varying from natural gas to grains and cooking oil.

Ankara has also tried to balance its relatively advantageous relations with Ukraine. In fact, alongside supplying Ukraine with armed Bayraktar TB2 drones for the past couple of years (based on a 2019 agreement to co-produce drones apt for bombing Russian convoys), Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu announced the official closure of the straits by saying “This is not a military operation; it is officially a state of war” after Ukraine had requested the straits to be closed to Russian warships.

The straits that connect the Black Sea to the Mediterranean (i.e. Bosphorus and Dardanelles) are under Turkey’s control, according to the 1936 Montreux Convention, which gave Turkey the right to prohibit access to them to “vessels of war belonging to belligerent powers” in a case of war (article 19). However, this might not be regarded as an effective measure, since the same convention allows the warships of littoral regions to return to their bases through the straits, thus their passage cannot be prevented.

Having positioned itself as a mediator, two negotiations are already held in Turkey, respectively one in Antalya and one in Istanbul.

“Ukraine made an offer on the collective security agreement: P5 (the UN Security Council’s five permanent members, China, France, Russia, Britain, and the US), Turkey and Germany,” to be a guarantor of any future deal with Russia, Çavuşoğlu said during a visit to Lviv and “I saw that the Russian Federation had no objection and could accept such an offer,” he added, after a meeting with his Russian counterpart Lavrov in Moscow. Furthermore, already hosting Syrian and Afghan refugees, Istanbul is now also hosting Ukrainian refugees (though most are directly crossing the neighboring land borders) along with anti-war Russians.

As the negotiations continue, sea traffic in Istanbul is currently at risk as it has recently been announced by the Turkish Ministry of National Defense that sea mines from Ukrainian shores are drifting towards the Bosphorus, and thus to the Mediterranean sea.

The global situation seems replete with deep contradictions and Russian diplomatic pragmatism might favor an unfortunate shift towards a more fragmented world and a more substantial presence of bilateral relations.

Just recently, on March 30th, the leader of South Ossetia stated that public consultations should be held regarding an annexation by Russia saying South Ossetia and the Russian Republic of North Ossetia should not “miss the opportunity” to unite under Russia. It’s feared that such an attempt would add to the political crises if not a new combat.

After the Russian-Georgian war in 2008 South Ossetia, along with another separatist region Abkhazia, was recognized by Russia as an independent statelet and Russian permanent military bases were stationed at each even though both regions are recognized as belonging to the Georgian by all UN member states but five.

Adopting a long-run perspective, we will thus see whether Europe’s political unity, its determination to diversify its energy portfolio and increase its spending on defense policies will still remain the pivot around which further geopolitical analysis should be conducted.

David is GZAAT Graduate and a sophomore at Bocconi University in Milan, Italy.