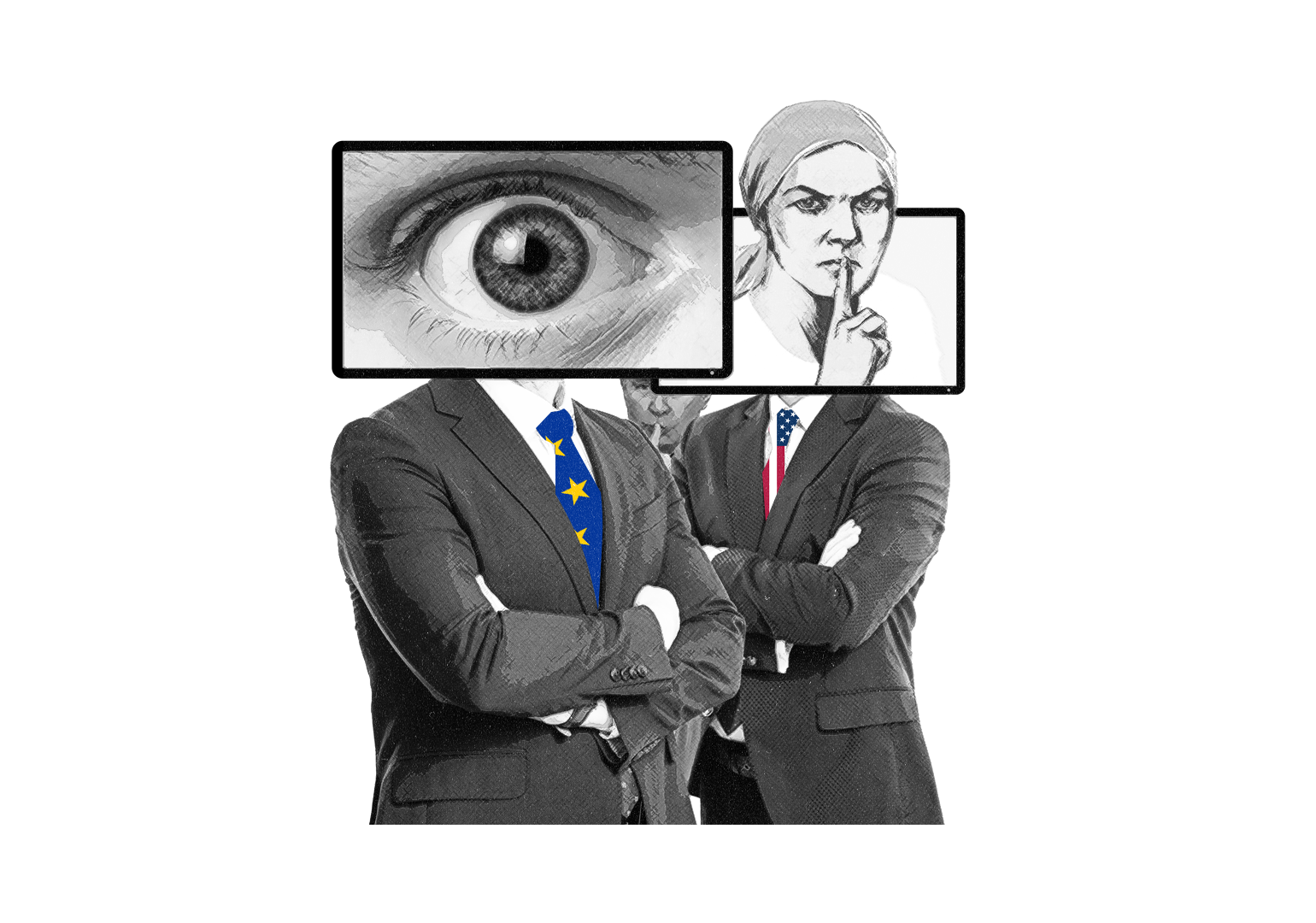

The Georgian Parliament has passed the “Foreign Agents Registration Act” in its third reading. Under the law, organizations that receive foreign funding and are involved in political activity must register as “agents” and publicly disclose their financial sources and personal data. This legislation replaces the previously proposed “Transparency of Foreign Influence” bill, which triggered widespread protests and drew sharp international criticism. Although the ruling party insists the new version is modeled after the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), experts argue it is a veiled attack on civil society and independent media. These fears stem from the government’s increasingly repressive measures, including restrictive amendments to laws on gatherings, demonstrations, and the media — all adopted by a parliament that was boycotted by the opposition due to flawed elections.

It all started in 2023, when the ruling Georgian Dream party and its satellite movement, “People’s Power,” introduced two draft laws: one on “Transparency of Foreign Influence” and another on the “Registration of Foreign Agents.” Following mass protests by citizens who dubbed the initiative a “Russian law,” Parliament ultimately rejected the bill.

In 2024, Georgian Dream reintroduced a revised version of the law that omitted the word “agent.” Despite renewed protests, Parliament passed the bill. This prompted harsh criticism from Western partners, who began reconsidering their cooperation with Georgia and imposed sanctions on individuals involved in violence against demonstrators. In an effort to prove that the law is modeled after the American FARA, Georgian Dream presented a verbatim translation of the U.S. FARA to Parliament on March 4, 2025.

See also: The New Law Against Media: Where the Georgian Dream Becomes a Reality

Who does the “Foreign Agents Registration Act” affect?

Robert Hamilton, Director of the Eurasia Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, points out that in the U.S., FARA applies strictly to entities involved in political activities on behalf of foreign governments. In Georgia, however, he warns that the law could be applied to “any organization the government chooses to target.”

The Georgian translation of FARA defines a “foreign principal’s agent” as someone acting under the “authority, request, command, or control” of the foreign principal. It includes any individual whose activities are directly or indirectly supervised, managed, funded, or subsidized — fully or largely — by a foreign principal, either directly or through intermediaries. A “foreign principal” is defined as any foreign government, political party, partnership, association, corporation, organization, or group operating under foreign law.

According to experts, this broad wording gives authorities wide latitude to label any critical media outlet or NGO — those that investigate corruption, question government policies, or conduct investigative journalism — as acting in the interests of a “foreign principal.”

“As a rule, independent NGOs and media organizations acting on their own statutes and free will are not listed in the U.S. FARA registry. That list includes entities controlled by foreign governments, such as Sputnik or Russia Today, but not BBC or Deutsche Welle — even though those are also funded by foreign states. The latter are recognized as independent and are not required to register,” explains lawyer Saba Brachveli from the Civil Society Foundation.

Before the new bill was even passed, over 100 organizations released a joint statement asserting that the U.S. FARA does not obstruct the work of NGOs or free media, while the Georgian government is trying to disguise a repressive law under the guise of Western standards.

“[Bidzina] Ivanishvili’s government claims it is introducing a direct translation of the 1938 U.S. FARA. However, unlike FARA, this law is not intended to regulate foreign influence but to repackage the previously rejected Russian-style bill targeting civil society,” the joint statement reads.

It is worth noting that the “Russian law,” to which these comparisons are often drawn, was passed by the Kremlin in 2012. According to Andrei Sharri, Director of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Russian Service, that law initially targeted NGOs and media, then expanded to include individuals who disagreed with Kremlin policies, ultimately becoming a tool for total censorship.

See also: Georgian Parliament Bans Receiving Grants Without Government Approval

The Georgian bill exempts diplomats, consular officials, and representatives of foreign governments and their staff. It also excludes academic, scientific, religious, or artistic institutions, as well as charities that receive foreign aid but are not involved in political activities. Still, experts argue this is further evidence that Georgian Dream’s recent laws aim to suppress dissent and consolidate power.

“Georgian Dream considers the introduction of the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) in the context of exercising oversight and control over civil society and media organizations. However, under any reasonable interpretation of FARA, such organizations should remain beyond the scope of its regulation,” notes the Social Justice Center.

Who will enforce the law, and what are the penalties for non-compliance?

According to the law, enforcement responsibility lies with the Anti-Corruption Bureau. In the U.S., this function is carried out by the Department of Justice. Experts argue that what makes the law “un-American” is how it is tailored to Georgia’s political environment — where enforcement is handled by agencies controlled by Georgian Dream, which could use the law for political leverage.

“FARA is not just a set of words — it’s defined by the way it is interpreted. In Georgia, they may adopt the words of the law but change the interpretation and enforcement practices entirely,” says Saba Brachveli.

The Social Justice Center echoes this view: “Simply copying the text of FARA without considering its judicial application and the series of rulings that clarify its content, standards, and principles will not guarantee its transplantation in our context.”

Under the law, individuals who knowingly violate its provisions or submit false or incomplete registration information may face a fine of up to 10,000 GEL (around $3,500), imprisonment of up to five years, or both.

As for the information required in the registration form, it must include the applicant’s name, status, principal’s business address, citizenship (if an individual), a description of the applicant’s activities, a list of employees and their responsibilities, the foreign principal’s name and address, details of financial support received in the past 60 days, a list of political and non-political activities, the names of persons or organizations represented, and copies of any partnership agreements.

Despite Georgian Dream’s claim of adopting a literal translation of the U.S. FARA, the move has only intensified public debate. While the government argues it is aligning with American standards, experts maintain that “the daily reality of the violation of freedom of expression and association, including the threats stemming from the implementation of the so-called “Russian law,” is irrefutable evidence that the Georgian Dream does not limit itself to reasonable interpretations of FARA. Moreover, protection from its instrumentalization by constitutional and legal standards cannot be ensured by the Georgian judiciary system, which will lead to irreversible consequences for civil society and democracy in Georgia”.

See also: Pro-EU Protests in Georgia