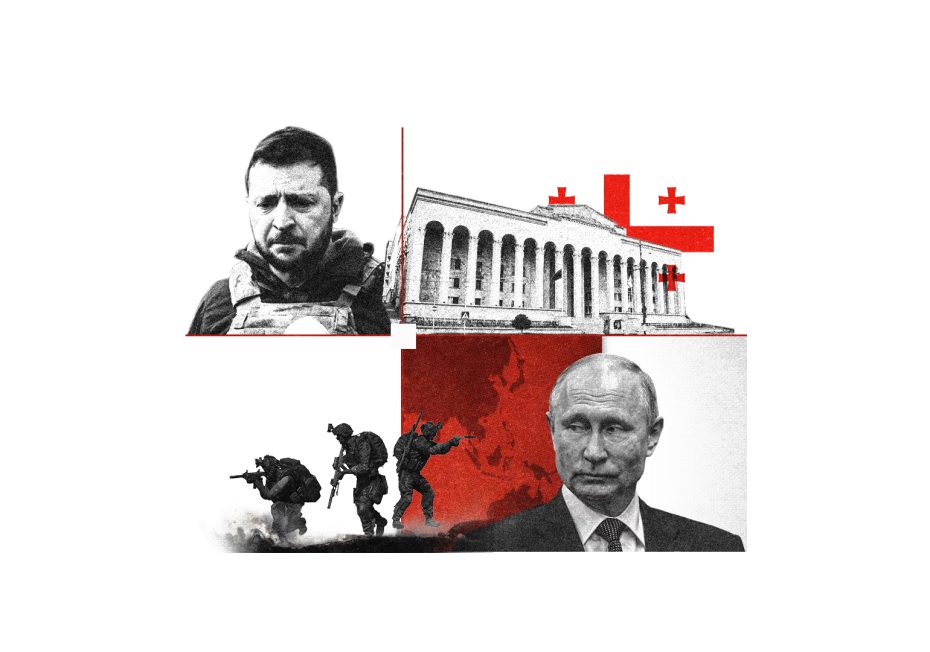

Georgia’s stance towards the on-going Russian aggression against Ukraine has been somewhat ambivalent. Even though the Georgian government condemns the war, it has not joined the anti-Russian sanctions. According to Kyiv, Georgia has been aiding Russia to circumvent its isolation from the West. While Georgia’s “neutrality” towards the Kremlin may be partly explained by the fear of a possible Russian threat, this stance still could be interpreted as support for Moscow. In the wake of the recent cooling relations between Tbilisi and the West led by democratic backsliding in Georgia, there is a possibility that the Georgian government might be gradually reorienting its foreign policy axis towards Moscow. Cooperation with internationally isolated Russia may bring short-term benefits for Tbilisi. Nonetheless, there can be security risks that can take effect in the long run.

In response to the Russian invasion, representatives of the Georgian government and President Salome Zurabishvili declared their solidarity with Ukraine. On 7 April, at the UN General Assembly Georgia joined the countries willing to suspend Russia’s membership of the Human Rights Council. Despite the supportive rhetoric, Tbilisi abstained from joining the sanctions imposed by the West. At the first glance, it seems that the main reason was not to draw the country into an armed conflict as Georgia could at any time become the next target of a Russian attack. However, the Georgian government might have seen Russia’s current troubles as an economic opportunity. While trade routes via Russia are closed and goods completely banned between the West and Russia, Moscow has sought to find alternatives in its bordering countries. This urgent situation created opportunities for these neighbouring states to take advantage of the Kremlin’s isolation and gain economic benefits. It has been considered by the Ukrainian government that Georgia has been allowing Russia to evade Western sanctions. In fact,

While there are no diplomatic relations between Moscow and Tbilisi, there have been some recent attempts to thaw relations. On January 18, at a press conference, Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov stated that he was glad that the contacts with Georgia were actively developing, and that Georgia’s GDP grew by 10 per cent in 2022 largely thanks to tourism and trade relations with the Russian Federation. In recent years, the Georgian economy’s dependence on its northern neighbour has increased noticeably. This is also connected to the massive influx of Russians who fled mobilisation or the effects of sanctions and repressive state measures. According to a report by Transparency International Georgia, even in 2021, for example, over 23 per cent of the gas Georgia imports (in 2018 it was just 2.8 per cent) and as much as 94 per cent of its wheat came from Russia.

Georgia has been accused of serving as a channel for Russia to avoid isolation as transit volumes between Russia and Turkey via Georgia skyrocketed in 2022. Moscow has somewhat close ties with Turkey and Ankara has not imposed sanctions against the Kremlin. Georgia is geographically the shortest route between the two countries. Kyiv and the Georgian opposition have accused the ruling Georgian Dream party of secretly colluding with the Kremlin. Nevertheless, the Georgian government insists that goods in transit through its territory are not subject to international sanctions.

It is worthwhile to mention that Moscow has also proposed resuming air links and even restoring diplomatic ties. This was not well-received among Georgians who were already critical of the government’s cautious stance vis-à-vis Russia. However, Irakli Kobakhidze, chairman of the incumbent Georgian Dream party stated that resuming flights would be important for Georgian fellow citizens living in Russia. The statement elicited a backlash from the opposition and the president, seeing the party chief’s stance as appeasing Moscow amid Russia’s on-going aggression against Ukraine.

Tbilisi may be playing a double game which can contribute to undermining Western efforts to cripple the Russian front. Amid Moscow’s international isolation, Georgia’s stance may be neutral on paper but it is de facto support for the Kremlin. This has been confirmed by the compliments Russian politicians have paid to the Georgian government. Georgian Dream’s stance may be led by pragmatism and strife for accruing short-term economic benefits. However, there are potential long-term costs that cannot be disregarded as even little dependence on the Kremlin could rapidly turn into geopolitical leverage. Another worrisome issue is the number of Russian residents and newly registered Russian businesses in Georgia. Since the beginning of the war, more than a million Russian citizens entered Georgia, while around 20 000 companies have been registered. Even though these developments might bring some short-term economic benefits, Georgia might find it hard to diversify its economy and decrease its dependence on Russia.