Introduction

At the time of writing this article, the COVID-19 pandemic is still unfolding globally and is on the rise in most parts of the world. Over 10 million people have contracted the disease in 215 countries, and over half a million people perished because of it. With already a grim outlook for the global economy, the full extent of the devastating economic and social effects of the pandemic is yet unclear. Beholding the historical experience of previous pandemics and following the advice of the experts, most of the governments are bracing for a potentially more disastrous second wave of the infection in the Fall.

There are still many unknowns and unanswered questions regarding the novel coronavirus and how it managed to inflict so much damage around the globe. However, enough time passed, and enough evidence accumulated for analysis and deliberations on the preliminary lessons learned from the global pandemic response. In some countries, the contagion spread like wildfire and their health systems collapsed. In contrast, others appear to be successful in controlling the outbreak and averting catastrophic results. Looking more closely to such country cases may give us an insight on why this wide variation among countries occurred; what were the determining factors that some countries and regions fared better than others, and more broadly, what so far has worked and what does not, in responding to the biggest challenge that humanity has faced in this century.

This paper presents a Georgia case study on the country’s response to COVID-19 pandemic, which the international media and professional circles have praised as effective[1],[2],[3]. The analysis below attempts to identify the prerequisites and factors that may have been very important, if not decisive, in curbing the COVID-19 outbreak in the country by the time of writing this paper.

We use Health Policy Triangle theoretical framework to describe when and what happened as the country mounted a policy response to the pandemic and identify some of the factors and prerequisites that may explain why and how the policy response to COVID-19 was designed, implemented and the observed results achieved. This framework stipulates that Health policies are formed through the complex inter-relationship of context, process, and actors. Walt and Gilson have proposed the health policy triangle[4],[5] as a way of systematically thinking about all the different factors that may affect policy (Figure 1). Policy formation falls into the process corner of the policy triangle and is influenced by actors, content, and context.

Context

Context

Both global and national contexts influenced Georgia’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The global context is particularly important, considering the global nature of the challenge requiring a domestic policy response.

Global context

In the past four decades, the emergence of new infectious diseases has shaped not only clinical concepts but also those of science and public health; affected political and policy responses at global, regional and national levels; had a severe economic impact, and profoundly influenced the anxieties and expectations of the public. The emergence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by the first novel coronavirus in 2003, the human to human transmission of avian influenza A (H5N1) demonstrated the speed at which an infectious disease, in this globalized world, can move beyond its local origins to become a global crisis affecting the health of people and economies by reducing international travel and trade. SARS and H5N1 became the driving forces for countries to reshape the International Health Regulations (IHR) and to adopt a revision in 2005. The regulations are an acknowledgment that all countries are at risk from specific threats, such as a new infectious disease with the potential for international spread. The IHR also stresses the need for a proactive approach by affected countries and the need for transparency in reporting. This approach encompasses the prevention, containment, investigation, and timely reporting of findings[6]. The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic demonstrated that a global outbreak of even a relatively mild disease could overwhelm the capacity of many countries to respond and raised several key issues. At the beginning of the pandemic, the naming of the virus (swine influenza) raised concerns regarding fairness and stigmatization. The naming issue, along with the rapid pace of developments and enormous amounts of information and misinformation, aided by social media and the Internet, created significant levels of distrust and anxiety among countries, the media, the public, individuals, and organizations. The pandemic eventually underscored that states are better prepared than in the past, but they still have much to do to be adequately prepared. Ebola outbreak in Africa in 2014-2016 reiterated the weaknesses in the world’s ability to prevent and contain a global health threat. The report commissioned by the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) in 2019 pointed out that “For too long, we have allowed a cycle of panic and neglect when it comes to pandemics: we ramp up efforts when there is a serious threat, then quickly forget about them when the threat subsides. It is well past time to act.”[7]

The emerging global response to COVID-19, caused by yet another novel coronavirus, clearly shows persisting gaps in the global health security mechanisms and the repeated mistakes, shortcomings,

and even failures, mirroring those from the previous pandemics. Specifically, many experts[8], and even governments[9], raised serious concerns regarding the timeliness and completeness of the information shared on the novel coronavirus outbreak by China, were new infectious disease originated and thus violating the information transparency obligation under IHR. The Associated Press’s investigation found that Chinese officials sat on releasing the genetic map, or genome, of the deadly virus for over a week after multiple government labs had fully decoded it, delaying for another two weeks sharing details key to designing tests, drugs, and vaccines[10]. The US government and several other countries (UK, Canada) also accused WHO in failing to timely act and communicate an early warning about the transmission of the coronavirus between humans, slowing the global response to the pandemic. The WHO’s decision to not recommend, and even advise against, the travel ban from Wuhan and quarantining the passengers that are not ill, was also criticized. Due to these alleged shortcomings, the US government even suspended funding to WHO[11]. Noteworthy that the Georgian authorities, contrary to this specific WHO recommendation, banned flights from Wuhan and mainland China on 29 January and have introduced mandatory quarantine for all Georgian citizens returning from China through other routes. Retrospectively, this appears to have been the correct mode of action to prevent the early spread of infection in the country. Many European Countries and the US were forced to introduce travel bans weeks later, thus missing the opportunities to prevent hundreds of imported infection cases.

The global context for COVID-19 response, particularly at the initial stage, was influenced by the implication that autocratic governments are better in tackling the infectious diseases because they have the ability to mobilize quickly and impose the necessary lockdown measures strictly. For example, China aggressively promoted its success in containing the outbreak and significantly lowercase fatality rate than democracies of Italy, Sweden, the UK, and the US. Russia, for a long time, reported fewer cases than any European democracy, and Turkmenistan reports zero infections to date. This implication is essential, as it may have a long-lasting negative impact globally and particularly for Georgia with its still emerging democracy long after the COVID-19 outbreak is contained. However, more careful analysis shows that this appears to be not true. On the contrary, the Economist argues that “most data suggest political freedom can be a tonic against disease.” Hence, comparative analysis of Georgia’s, as a young democracy’s performance in the COVID-19 response with other transition countries and with autocratic governments, gains a whole new meaning.

Another essential global contextual factor that contributed to the flaws in global and country-level response was the absence of epidemiological models that can reliably predict the COVID-19 outbreak scenario and design adequate policy responses[12]. Potential reasons for the failure of COVID-19 forecasting in many countries included an absence or poor quality of information on key characteristics of the novel coronavirus that go into theory-based forecasting. The poor quality of inputs resulted in wrong assumptions in the modeling mainly based on the past outbreak experiences that turned out to be irrelevant for COVID-19. For example, the basic reproduction number[13] in most pandemic models was estimated at a maximum of 2. In contrast, the COVID-19 reproductive number

is currently estimated to have been almost three times higher than that figure at 5.7[14]. In other words, it means that the novel coronavirus is far more transmissible than assumed in the pandemic models. In the absence of solid modeling, particularly at the earlier stage of the pandemic with many unknowns, policymakers have faced difficult dilemmas and often impossible decisions while designing appropriate policy interventions to counter the outbreaks in their countries[15]. The uncertainties in forecasting were compounded by sparse past evidence on the effects of available interventions, including the mobility restrictions.

The COVID-19 response highlighted the importance of the global movement to build stronger health systems to achieve universal health coverage (UHC). Universal health coverage is defined as ensuring that all people have access to needed health services (including prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation and palliation) of sufficient quality to be effective while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user the financial hardship[16]. When outbreaks are big enough to overwhelm health-care systems, deaths soar, since even cases that might respond to treatment, become deadly. Poor countries have fewer hospitals and doctors and less of the necessary kit, from ventilators to disposable gloves and gowns. With the pandemic-induced crisis expected to deepen before it improves, there are some foundational issues relating to health systems and people’s access to health services that determine how successful are individual country policy responses to this global health threat. Households increasingly face financial strain as the COVID-19 outbreak becomes an economic crisis in many countries. If people face concerns about health care affordability, they may delay seeking treatment or be prevented from obtaining the services they need, making the outbreak harder to control. That’s why, according to the International Partnership for Universal Health Coverage 2030 (UHC2030), “Right now, health systems and UHC are what will make the difference to each country’s response to COVID-19. They affect whether all or only some receive treatment, as well as rates of recovery and the level of protection afforded to health workers.”[17] In recent years G7 and G20 leaders promoted strong and resilient health systems as vital for both UHC and health crisis management, which are “two sides of the same coin.”[18] The UHC2030 Key Asks applied in the context of COVID-19 are mutually reinforcing and include the call for bold political decisions and responsible leadership at the highest level, as governments need to prioritize health crisis preparedness and response as public goods, more investments in health systems and removing financial and other barriers that prevent access to relevant information, appropriately prioritized testing, or treatment for COVID-19[19]. The global context of interlink between UHC and COVID-19 is particularly relevant for Georgia, where the 7-year old political and policy commitment to UHC in the realization of the health as a fundamental human right has, in our opinion, played an important role in ensuring adequate pandemic response.

National context

The two most critical contextual factors contributed to shaping the COVID-19 policy response in the country: macroeconomic and health system resilience. Georgia, with its young democracy and transition economy, is generally vulnerable to any outside shock. The last six months have demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic is a major global threat capable of delivering a devastating blow to economies, health, and social systems of the leading industrialized countries when not properly contained. The national lockdown used to prevent the spread of the virus in the absence of an effective vaccine is a double-edged sword, – while one edge disrupts the virus transmission chain, another edge destructs the economic and social ties within the society and if used for the extended period leads to even more poverty, suffering, and deaths, than direct health results of the infection. Georgia does not have macroeconomic resilience to withstand the economic shock of such magnitude that uncontained COVID-19 and/or extended national lockdown to prevent its spread may have. When initial mobility restrictions were introduced, the Georgian currency plummeted to the historical minimum, with looming inflation threat. Tens of thousands of temporary and permanent jobs were lost or endangered. The Government of Georgia (GoG) was even more constrained than stable economies in its ability to both deepen and extend the mobility restrictions and the lockdown, attaching vital importance to the early and targeted application of the infection containment measures and an effective health system response.

An effective health system response in public health emergencies depends on a system’s readiness for a specific disaster (pandemic in this case), and resilience to adapt and withstand shocks. In terms of health system readiness for COVID-19, we look at two key factors: preparedness and response plans and core capabilities to detect and respond to outbreaks. According to Handfield et al., resilience depends on three core dimensions corresponding to three health systems functions: “health information systems” (having the information and the knowledge to make a decision on what needs to be done); “funding/financing mechanisms” (investing or mobilizing resources to fund a response); and “health workforce’ (who should plan and implement it and how). These intersect with two cross-cutting aspects: “governance,” as a fundamental function affecting all other system dimensions, and predominant “values” shaping the response and how it is experienced at individual and community levels[20]. The three dimensions of resilience are also part of the health system preparedness and response capabilities: health information systems, adequate financial resources/funding, and health workforce, along with the surge capacity (health care infrastructure and equipment) required to accommodate the increased patient workload during the outbreak.

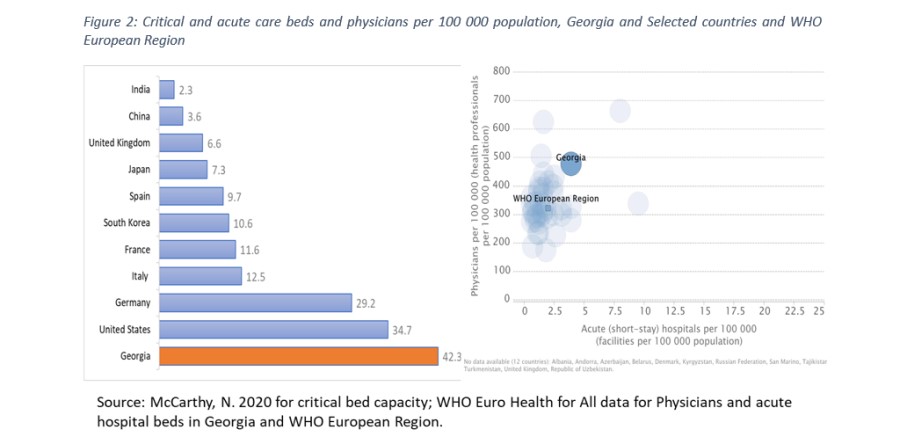

Georgia has in place pandemic influenza preparedness plans and appropriate legal and policy framework and emergency funding mechanisms to respond to outbreaks and biological incidents effectively[21]. This framework and most importantly, the key outbreak response capabilities – NCDC’s G. Lugar Center for Public Health Research and its surveillance and laboratory capacities and public health workforce: health planners, epidemiologists, laboratory personnel, who were the “national frontrunners in the battle against the coronavirus”[22] were critical for the country’s COVID-19 response[23]. Equally important were the cadre of infection disease specialists, intensive care physicians and nurses, nurse aides, medical students-volunteers, who have been “first responders” on the medical “frontline” against COVID-19. In terms of the critical infrastructure and equipment needed for an effective COVID-19 response, the country has 2,290 critical care beds[24], or 61.9 beds per 100,000 population, with 1,749 ventilators approved for the management of the respiratory distress syndrome[25] (the most common and dangerous complication of the COVID-19). Georgia’s critical bed capacity, even when adjusted by the number of ventilators available, considerably exceeds that of the world’s leading nations. Georgia also ranks among the top five countries in the WHO European Region by the number of acute (short stay) hospital beds and the number of physicians per 100,000 population (see Figure 2). According to the GoG, Georgia’s 488 certified intensive care specialists, in case of COVID-19 cases surge, can be mobilized to fully staff 1,200 critical care beds with mechanical ventilators[26], providing considerable surge capacity for the country to respond to the pressure on health care system adequately.

Based on the GoG report on COVID-19, Georgia’s health information system provided the necessary information for decision-makers in a timely manner. More specifically, the COVID-19 case notification system functioned without any visible flaws. Epidemiologists timely identified more than 3,400 contacts for a total of 700 confirmed cases (by the end of May). NCDC has re-oriented a sentinel surveillance system for seasonal influenza to detect SARS-CoV2 to control the status of the COVID-19 community transmission, even before the first case confirmation in Georgia. On 16 April 2020, the GoG has introduced a new mobile phone application for voluntary use. This application is an important tool for tracing contacts of coronavirus-infected persons and for preventing the further spread of the virus, enabling its users to find out whether they have been in contact with COVID-19-infected persons[27]. The Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs (MIDPOTLHSA) established a live tracking of admitted and discharged COVID-19 patients and vacant beds in COVID-19 dedicated clinics[28].

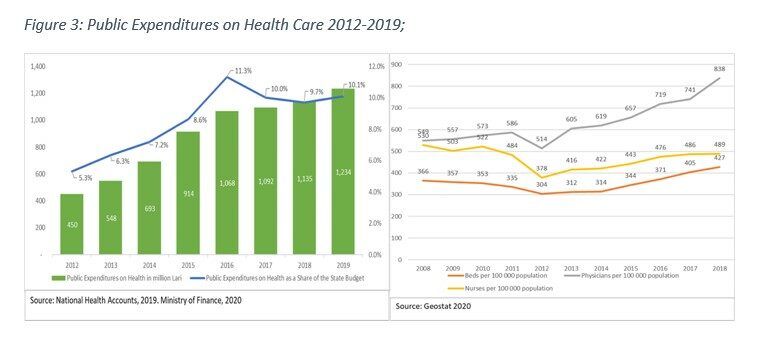

Finally, the two cross-cutting aspects of health system resilience in Georgia, the system governance and values are intrinsically tied to the country’s long-term policy aspiration to achieve UHC. For the ruling party the Georgian Dream (GD), the introduction of the UHC program in 2013 is one of the major achievements since it won the national elections in 2012. This achievement is recognized internationally[29], and despite certain implementation and efficiency concerns that emerged in the program recently, almost every public opinion or experts’ poll for the last seven years also shows continuing support to sustainment and further expansion of the UHC[30],[31],[32]. The GD government regards the UHC as a unique opportunity to practically realize the right to health[33] enshrined in the WHO constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights and European Social Charter to enable persons to enjoy the highest possible standard of health attainable[34]. Since regaining independence in 1991, health care was a low policy priority and was financed with a “residual principle” – what was left from other priority sectors, such as public safety, defense, infrastructure, etc.[35],[36] With the introduction of the UHC, health care gained a high political priority, and the health budget almost tripled in absolute terms. It doubled as a share of the public budget, making health a clear budget priority in the period from 2013 through 2019 (Figure 3).

Increased public expenditures not only removed financial barriers to utilization of essential services and prevented impoverishment of tens of thousands of Georgian citizens due to the catastrophic health expenditures but also attracted over 1.4 billion Lari (app. $620 million)[37] in private capital investments in health care infrastructure and equipment. As a result, the resources (beds and medical personnel) available for health care have progressively increased in the same period surpassing the per capita health sector capacities of most countries in the world. In the pre-pandemic period, this trend resulted in excess capacity and a perceived inefficiency of the hospital sector: despite the increased volume of services, hospital bed occupancy rates across the nation never exceeded 50-52%[38]. Once COVID-19 emerged, the excess hospital infrastructure and personnel transformed from the negative aspect of the Georgian health system into a positive contributing factor to health system readiness: Policymakers had far greater possibility to plan and mobilize surge capacity and health personnel contingency plans for the COVID-19 response than they would have had if Georgia’s health sector operated at maximum efficiency, as was the case in the UK and many states in the US[39]. Furthermore, we believe that high political priority of health in policy making sustained over the years contributed to the crucial decisions made at early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in the country, “tipping” the scales in favor of public health considerations, when the choice appears to be between the lives and livelihoods.

Content

The COVID-19 response policy in Georgia draws on several blocks of measures included in the Decree of the Government of Georgia #164 dated 28 January 2020 on “Approval of Measures to Prevent the Possible Spread of the New Coronavirus in Georgia and Approval of an Emergency Response Plan for Cases Caused by COVID-19”.

The following strategic objectives are defined in the Plan:

- Country preparedness for expected threats in case the disease is imported;

- Measures to prevent or reduce the effects of imported and local transmission;

- Support efforts to meet international regulations (WHO) to stop, slow down, restrict and report the outbreak of COVID-19;

- Mobilizing health care systems for the treatment and assistance of patients with COVID-19 through the continuing provision of essential health services to the population;

- Continuous provision of public information and media engagement[40].

To address these objectives, the GoG planned the following health system response measures:

- Control imported cases and clusters and prevent community transmission by rapidly finding and isolating all cases, providing them with appropriate care, and tracing, quarantining, and supporting all contacts.

- Mobilize all sectors and communities to ensure that every sector of government and society takes ownership of and participates in the response and in preventing cases rough hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and individual-level physical distancing.

- Suppress community transmission through context-appropriate infection prevention and control measures, population-level physical distancing measures, and appropriate and proportionate restrictions on non-essential domestic and international travel.

Reduce mortality by providing appropriate clinical care for those affected by COVID-19, ensuring the continuity of essential health and social services.

More details of the COVID-19 policy content and status of their implementation is presented in the GoG report on Measures implemented by the Government of Georgia against COVID-19 published in May 2020[41] and at the website of the Health System Response Monitor maintained by the WHO European Regional Office, which also provides a comparative analysis of the COVID-19 response for the member countries[42].

Actors

The COVID-19 response in Georgia was planned and proceeded as a concerted effort of multiple actors, international and domestic.

National Actors

Prime Minister Gioirgi Gakharia chaired the Interagency Coordination Council (ICC) and later the Operational Headquarters on the Management of the State of Emergency coordinated overall response planning and implementation. Deputy Prime Minister Maia Tskitishvili served as a deputy chair of the ICC and coordinated logistical aspects. Minister of Internally Displaced Persons from Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs Dr Ekaterine Tikaradze and the First Deputy Minister Dr Tamar Gabunia led the health system response assisted by the NCDC leadership Dr Amiran Gamkrelidze and Dr Paata Imnadze and Dr Avtandil Talakvadze, Director of the Emergency Situations Coordination and Urgent Assistance Centre. These bodies were and are responsible for the implementation of the Plan in compliance with International Health Regulations: coordinating surveillance, risk communications, international reporting, testing, and clinical management. Dr Tengiz Tsertsvadze led the clinical response team responsible for the national treatment protocols. Ministry of Interior was responsible for public safety and observance of rules of emergency state and curfew. In guaranteed regions and zones, the Ministry of Interior was assisted by the Minister of Defence and the armed forces. Regional Governors coordinated the regional operational headquarters and together with local government and self-government representatives, all activities in the lockdown regions and municipalities.

While public agencies coordinated the COVID-19 response, private sector actors played defining roles in the response. First and foremost, the individual citizens, who listened, complied with strict mobility restrictions, observed the rules, demonstrated compassion and solidarity towards the most affected – poor and elderly, those that lost jobs and subsistence. Every fifth Georgian family, already having low income, have experienced further drop as a result of the pandemic lockdown[43]. The Georgian Citizen was the key actor who ensured the effective COVID-19 response. Private actors in Georgia dominate the health sector (about 86% of the hospital capacity is private), and no health system response would have been possible without an effective public-private partnership. Private operators of essential services and infrastructure have been most exposed and on the frontline of the COVID-19 response. Businesses from other sectors were either the ones the most affected, as their operations were suspended for two months and had to incur additional expenses for complying with new regulations after reopening. Private businesses also mobilized financial resources for AntiCovid Fund, where over 133 million Lari was accumulated, the lion share of which, – 100 million, was provided by the wealthiest citizen of the country and chair of the ruling party Mr. Bidzina Ivanishvili. NGOs (for example, Red Cross), community organizations, and volunteer groups have carried significant humanitarian efforts for those in need and actively participated in the public awareness campaigns.

International Actors

The roles that global organizations such as WHO and other United Nations (UN) organizations, European Union (EU), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), US CDC, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and Georgia’s strategic partner countries were and are playing in policy formulation to global threats affecting the country. To name few: WHO provided invaluable support in preparedness and readiness measures, assisting with the response planning, theoretical trainings and practical exercises for enhancing the infection control and response activities, provided technical guidance for all aspects of the health system response. IMF disbursed emergency assistance facility and thus facilitated other multilateral and bilateral partners’ assistance to the country. The World Bank and ADB provided emergency project funds for immediate response measures and will be preparing larger projects for the long-term recovery. The US government assistance through the Defense Threat Reduction Agency and the US CDC over the years was crucial in creating the response capabilities at NCDC and its Lugar Center. The US funded programs produced hundreds of qualified epidemiologists, laboratory specialists and public health planners, who have been on the frontline of the COVID-19 response not only in Georgia, but throughout Caucasus. Czech Development Agency assisted in the retraining of more than 1,000 primary health care doctors in infection control and COVID-19 management.

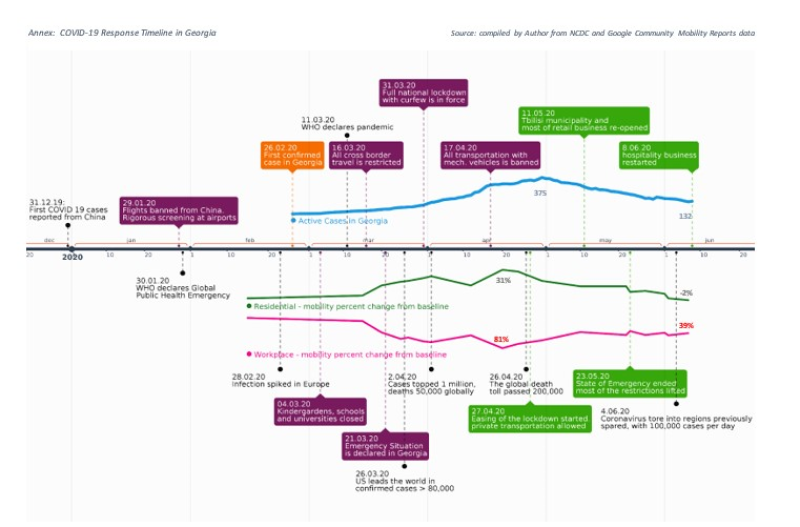

On 31 December 2019, the government of China confirmed, and the world learned that Wuhan health authorities were treating dozens of cases with the previously unknown, novel coronavirus. On 6 January 2020, the MIDPOTLHSA of Georgia has alerted the Government of Georgia regarding the novel coronavirus and started adjusting the country pandemic preparedness plan to the newly identified virus.

By 20 January, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand confirmed the first cases outside China. Eight days later, the GoG approved pandemic preparedness plan and established a special task force for coordinating COVID-19 response – Interagency Coordination Council. The authorities imposed mandatory 14-day quarantine for all passengers returning from China (See Annex). The isolation requirement was later extended to Italy, France, Germany, and other European countries, and rigorous thermal screening was introduced for all border checkpoints. The active response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Georgia started on 25 January 2020, when emergency medical teams equipped with C-level Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and remote thermometers were placed at seven key points of entry. This was seen as part of Georgia’s responsibilities as a party to the International Health Regulations, guided by the recommendations of WHO and the ECDC[44]. By 30 January, the Lugar Laboratory of NCDC developed testing capabilities identifying COVID-19 carrier – SARS-CoV-2, approved the COVID-19 case national definition, and testing, prevention and treatment national guidelines. The GoG launched a full-scale public awareness campaign.

On 30 January, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19 outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern alerting the global community and calling for concerted international action. Fourteenth of February, France announced the first death in Europe, and Iran experienced a surge of COVID-19 cases. Two days later, Georgia suspended travel from Iran. Yet, on 26 February, registered the first confirmed case in Georgian citizen with travel history from this country (see Annex).

From 28 February, the infection started to soar in European countries, Italy, Spain, France, Switzerland, and Belgium were among the most affected. Based on the recommendations issued and the experience available so far, countries began implementing non-pharmaceutical measures in response to the spread of COVID-19. These measures included: closing educational institutions and transitioning the educational process to a remote mode of operation, banning mass and public gatherings, restricting individual economic activities, physical distancing, and declaring a state of emergency throughout the country, which included the implementation of strict quarantine measures and a curfew. However, in most countries, these mobility restriction measures were taken when the confirmed cases reached thousands. For example, when France imposed a nationwide lockdown on 17 March, the country had more than 6,500 infections, with more than 140 deaths. The United Kingdom adopted similar strict measures a week later, 23 March, after a short-lived attempt of a laissez-faire approach to COVID-19 control resulted in 6,650 confirmed cases and 335 deaths[45].

After the first registered COVID-19 case, Georgia progressively escalated the mobility restriction measures until the President declared, and the Parliament approved the state of the national emergency on 21 March. The country went in full lockdown with a curfew on 31 March. The lockdown included the suspension of all international travel, intercity, and municipal transportation, all educational, cultural and business activities (except essential services, and operations of critical infrastructure), bans on public events and mass gatherings of more than three individuals and stricter “stay home” orders for individuals aged over 70 years. Several large municipalities with higher epidemiologic risk were quarantined. The GoG embarked on all these measures when less than 100 cases and no COVID-19 induced deaths were registered in the country. In doing so, the GoG followed recommendations from the national health authorities, epidemiologists, and public health experts stemming from the guidance of WHO, the US Centers for Diseases Control (CDC) and ECDC.

By 2 April, the pandemic had sickened more than one million people in 171 countries across six continents, killing at least 51,000. The US began to lead the world in confirmed cases. Cases surged in Russia and Turkey, two of Georgia’s largest neighbours. Widespread national lockdowns imposed in the leading economies in April dramatically worsened the global economic outlook. The IMF concluded that the world was heading towards the worst downturn since the Great Depression and called it “The Great Lockdown.”[46] Georgia also experienced the acceleration of daily confirmed infection cases and recorded three COVID-19 related deaths.

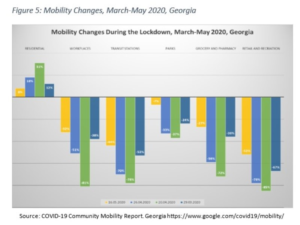

By mid-April, with a continued increase in the headcount of infected and with the first suspected community transmission[47] case of COVID-19, and in anticipation of potential massive violations of mobility restrictions and physical distancing rules during the celebrations of the Orthodox Easter on 21 April, the GoG further tightened the lockdown by prohibiting all mechanical transportation (other than by motorcycles) and entering or exiting four major cities of the country, including the capital Tbilisi, by any means of transport. Wearing face masks in enclosed public spaces became mandatory. Public messaging and risk communication intensified. Judging from the Google Community Mobility Reports (see Figure 5), these extreme measures indeed had the desired impact on community mobility in Georgia. Almost one-third increase in the share of population staying at home, and respectively 81% and 85% decreases in the people’s presence at workplaces and public areas (retail and recreation) in the week of 20 April, compared to the baseline[48]. It appears that the citizens’ confidence in the GoG, the ICC and MIDPOTLHSA and in their decisions in curbing the outbreak, contributed to this high compliance to the restrictions.[49]

By 26 April, more than 2.6 million individuals infected worldwide, and the global death toll due to COVID-19 reached 200,000. Italy has seen 25,000 deaths. Spain has suffered 22,000 fatalities, France has 21,000, and the United States has lost 46,000. By the same day, Georgia had under 500 confirmed cases and five COVID-19 related deaths. Twice as many Georgian nationals died abroad in Italy, Spain, and the US. The GoG began repatriation of the Georgian citizens, who were trying to escape from the worst affected European countries, where many Georgians went for better education or employment opportunities before the pandemic distorted the world.

In the absence of widespread community transmission, with daily case numbers dropping below 30 and the effective reproduction number Rt[50] estimated at under 0.5[51], – the GoG started easing certain restrictions from 27 April (see Annex). After reaching the peak on 1 May at 375, the number of active COVID-19 cases began to decline and continued this trend after the lockdown and the state of the national emergency ended on 23 May. The number of active cases was down to 132 as of 10 June. By mid-June, the GoG has removed almost all mobility restrictions, with the exemption of the ban on mass gatherings of more than ten individuals, operation of open agrarian markets, and cross border travel for foreign nationals. Reopening of the air travel for visitors and tourists, which is vital for the Georgian economy is only expected by 1 August. The final decision will depend on the epidemiologic situation in the region and Europe. Building on the demonstrable results of taming the COVID-19 outbreak, the GoG is determined to promote the country, not only as a safe tourist destination already known to more than 9 million visitors from the pre-coronavirus world in 2019, but also as a safe retreat for this summer[52] from the coronavirus havoc that still reigns in most parts of the world.

In the absence of widespread community transmission, with daily case numbers dropping below 30 and the effective reproduction number Rt[50] estimated at under 0.5[51], – the GoG started easing certain restrictions from 27 April (see Annex). After reaching the peak on 1 May at 375, the number of active COVID-19 cases began to decline and continued this trend after the lockdown and the state of the national emergency ended on 23 May. The number of active cases was down to 132 as of 10 June. By mid-June, the GoG has removed almost all mobility restrictions, with the exemption of the ban on mass gatherings of more than ten individuals, operation of open agrarian markets, and cross border travel for foreign nationals. Reopening of the air travel for visitors and tourists, which is vital for the Georgian economy is only expected by 1 August. The final decision will depend on the epidemiologic situation in the region and Europe. Building on the demonstrable results of taming the COVID-19 outbreak, the GoG is determined to promote the country, not only as a safe tourist destination already known to more than 9 million visitors from the pre-coronavirus world in 2019, but also as a safe retreat for this summer[52] from the coronavirus havoc that still reigns in most parts of the world.

Conclusions

While the COVID-19 pandemic is still far from conclusion, certain preliminary conclusions can be derived from the preceding analysis of the Georgia policy response: The global response to the novel coronavirus, particularly at the early stage, was flawed, repeating some of the same mistakes made during the previous outbreaks. WHO, as a coordinator of international response efforts, allegedly has not applied adequate effort for timely acquirement and verification of the accurate information regarding the emerging threat, which may have contributed to the delayed preventive measures in some countries currently most affected by the pandemic. In this context, the Georgian authorities were able to assess the threat adequately and contrary to the WHO advises, – ban air travel from China and introduce mandatory quarantine for travellers returning from the outbreak hotbed. Since then, over 20,000 individuals, mostly travellers (Georgian citizens returning home) and their contacts were quarantined by the first week of June[53].

The decision-makers in Georgia and elsewhere, when designing response policies, faced higher political risks due to the uncertainty in forecasting and poor past evidence on the effects of available interventions, including the mobility restrictions. In such conditions, with people’s lives and livelihoods at stake, decision-makers in Georgia appear to have unconditionally prioritized the population’s health and had strong confidence in health experts and authorities to follow their recommendations on “draconian” lockdown when only a few cases were confirmed in the country[54]. The GoG introduced non-pharmaceutical measures with uncertain (at that time) effects on infection spread, but easily anticipated detrimental economic and social effects. Political risks associated with such policy decisions were even higher, considering the upcoming parliamentary elections in Fall 2020 when any mistake in managing the COVID-19 and its health, economic and social effects on the Georgian people would have had dire electoral consequences for the GoG and the ruling party. For these reasons, many decision-makers in the governments around the globe (for example, the US, the UK, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Belarus, Brazil, Russia) either opted out or delayed radical mobility restriction measures.

Well aware of the imminent negative economic and social repercussions, the Government of Georgia has shown political courage in taking grave and unpopular decisions by swiftly and strictly adhering to the public health experts’ recommendations. This may not have been possible if the governance and values of the GoG have not been shaped by the long term political and policy commitment to health as a fundamental human right and UHC as means for realizing this right.

These decisive early actions of the GoG most likely saved lives, by preventing the import and slowing down the spread of infection and have provided more time to the health sector to prepare for the arrival of COVID19: to ready emergency response systems; to increase capacity to detect and care for patients; to ensure hospitals have the necessary staff, supplies, structure and system and necessary surge capacity is available.

Planning the adequate surge capacity and timely mobilization of necessary medical personnel would have been most likely impossible without the infrastructure and workforce capabilities created by the private investments in the health sector response to the major increase in public finances on health through the UHC program. These investments also helped to enhance the overall resilience of Georgia’s health care system.

The preparedness and response legal framework developed over the years and most importantly, the key outbreak response capabilities – NCDC’s G. Lugar Center for Public Health Research and its surveillance and laboratory capacities and public health workforce: health planners, epidemiologists, laboratory personnel, were critical for the country’s COVID-19 response. This was achieved with the continuing support from the US Government, the World Bank, and other international partners.

Georgia case shows that democratic states, even the emerging and young democracies, are well capable of mounting an effective response to the pandemic by adopting decisive and often unpopular actions. This case contributes to the body of evidence against the myth of autocratic states being more efficient in pandemic response.

The GoG demonstrated effective coordination and the ability to take “right actions at the right time prioritizing the right to health,” which were supported by the general public and may serve as a summary explanation of why Georgia was able to retain the “containment edge” for the epidemic so far. Law-obedient, understanding, compassionate, and patriotic Georgian Citizen is the main actor who made this achievement possible.

In the few weeks since the phase-out of some of the response measures, the active cases continued to decline in Georgia, and no rapid or major increase in incidence has been observed in the European countries and the UK[55]. However, the example of several countries, including the Georgia neighbours, shows the dangers of “overrelaxation” and lost vigilance when dealing with the novel coronavirus. The national health authorities need to continue active risk communication constantly reminding the public of the fragility of the current achievements in the fight with COVID-19 until the effective vaccine becomes available for everyone.

[1] http://georgiatoday.ge/news/20531/Top-10-Articles-in-International-Media-about-Georgia, seen on 05.07.2020.