It would not be demeaning to say that agriculture will not make a country rich. After all, the same could be said about any single sector of the economy, unless the sale of large quantities of oil is involved.

A country is enriched by the simultaneous growth of several of its sectors, including but not limited to agriculture or any other individual sector alone.

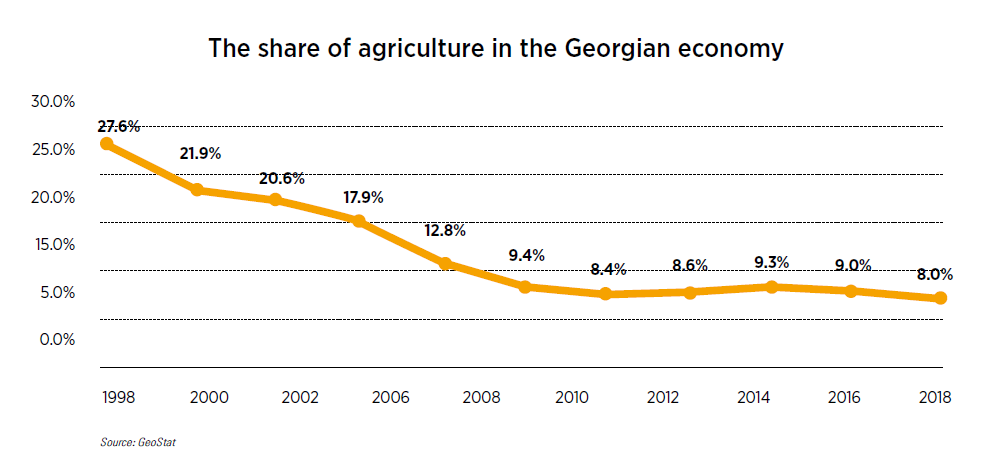

Politicians and others frequently cite agriculture as one of the main sources of achieving economic growth. However, the results show the opposite. In 1998, agriculture accounted for a 28% share in the country’s economy. That figure fell to 9.4%by 2008, and to 8% by the middle of 2018.

A decrease in the share of agriculture in a country’s economy does not necessarily imply that the situation is bad. The share of agriculture in every developed country’s economy fell as they went through certain stages of development. The quicker the pace of development, the quicker the fall in the share of agriculture. Although the agriculture sector was also developing on its own, other areas were simply developing at a much faster pace, leading to the aforementioned decrease.

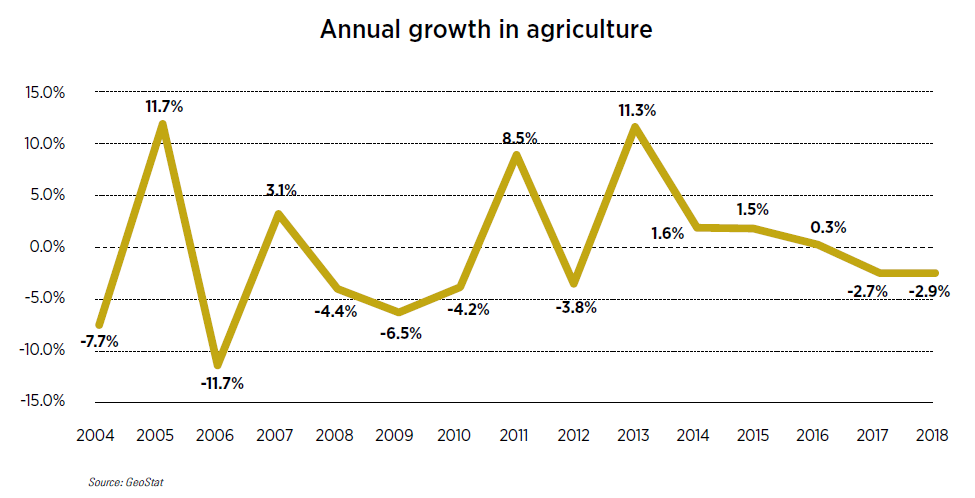

In Georgia, agriculture is not even growing on its own, meaning that year-by-year production in the sector is not increasing. If we look at production in this sector at constant prices (ensuring that price increases that are caused by inflation are not regarded as an increase in productivity), we see that production in the Georgian agriculture sector was worth H1.9 billion in 2003 and H1.8 billion in 2017.

From 2004 to 2018 (based on data from the first half of 2018), the average growth rate of the agriculture sector was -0.4%. Every government prioritized agriculture and operated a Ministry of Agriculture that spent considerable funds on efforts to develop it. In 2013, funding for agriculture was increased even further. The Free Tillage program proved particularly productive, leading to 11.3% growth in the sector in 2013. However, in 2014-2015, the growth rate fell to 1.5%, while in 2017-2018, the agriculture sector shrank by approximately 3% per year. Post-2016 production fell by H100 million. The total area under crops decreased, as did the livestock numbers.

Overall, the government spent in excess of H1 billion on supporting agriculture between 2013 and 2018. These funds were allocated to projects such as cheap agricultural loans, free tillage, enterprise funding, the Plant the Future project, the Georgian Tea Revival Program, agricultural insurance, subsidising the prices of grapes and citrus fruit, agricultural machinery, as well as scientific research. An additional sum of H300 million was spent on renovating and building irrigation infrastructure.

In addition to state spending, we have been able to export produce to the European Union and many other countries free from customs duties. In 2013, Russia lifted its embargo on Georgian agricultural produce. Numerous donors have been helping the agricultural sector with grants and expertise. Against this background, we really must ask ourselves how we managed to achieve a decline instead of growth in Georgian agriculture.

The answer lies in the wrong economic policies pursued by the state. We could not decide what we wanted – a rural population with a good income, or a rural population whose primary function is to live in rural areas and receive support from the urban centers?

It is a well-known economic fact that if the state subsidizes a sector, then there is a high possibility of that sector becoming used to being subsidized and finding itself unable to grow. This may be one of the roots of the problem in Georgia. Furthermore, the moratorium on the sale of agricultural land to foreign nationals clearly had a negative effect on the development of agriculture. This is not up for debate. It is simply the case that a section of the country’s population prefers Georgian land to be owned by Georgian nationals, rather than for us to have a larger agricultural sector.

The two aforementioned circumstances are economically wrong, but they may be politically justified (with a view to obtaining votes). Therefore, both approaches will be changed quickly when the political background allows us to do so.

A far bigger problem is presented by the wrong general approach towards developing the sector. Land is scarce in Georgia, with an average of approximately 1 hectare per family in rural areas. This is partly due to low levels of urbanization in the country, with 42% of the population (1.6 million people) living in rural areas. Scarcity of land leads to the ineffective use of the available plots. It is difficult to offset the sale of products at lower prices by the volume of production (scale effect), or to transform a small family enterprise into a medium-scale or large farming enterprise. Additionally, there is a lack of expertise, which is a problem that is not limited to agriculture.

At this time, the national policy is aimed at trying to increase the rural population for the simple reason that it could at least support itself by working the land. 700,000 people living in rural areas are regarded as self-employed, as they grow their own food and/or keep livestock.

We are therefore facing a certain dilemma: we are trying to end small land ownership, and simultaneously ensure that a lot of people live in rural areas. The golden middle would be for people to reside in rural areas while not working on land, which is not unrealistic. Resolving this dilemma requires the rapid development of other sectors. Thereafter, people will themselves decide where they want to live. Urbanization levels in developed countries currently reach the 70-80% mark, while agriculture accounts for no more than 5% of employment (in Georgia, the figure is approximately 40%). Villages in developed countries are more prosperous and well looked after than ever before.

The problem of a lack of agricultural expertise does not need to be viewed separately, as we are facing similar challenges in every area. Addressing the general problem of education would allow agriculture, along with many other sectors, to reap the benefits.

To summarize, the picture looks as follows:

1. In order to subsidize agriculture (any funds spent in this field, even to build irrigation systems, constitute a subsidy), the government is channeling too much money away from the sectors that are supposed to provide employment for the rural population.

2. Life in rural areas requires more subsidies than urban life. More urbanization is needed to solve the problem, yet the government is actually spending money on hindering urbanization.

3. The moratorium on the sale of agricultural land to foreign nationals has stopped the flow of investment, new expertise and technologies into the sector.

4. As with the other sectors, agriculture is suffering from a lack of knowledge and expertise. Moreover, obtaining education in the field of agriculture is not considered prestigious, and it is therefore unlikely that even a few individuals out of a thousand will obtain the appropriate expertise, as is the case with lawyers, doctors or economists.

5. Approximately 95% of the global economy is taken up by manufacturing and services, yet we are still attaching our hopes to agriculture. This is due to the fact that our knowledge and business environment only allows us to compete in areas where our advantages are conditioned by climate, soil and vegetation, rather than by education and effective work.

6. Development policy for agriculture (as well as other sectors) is determined by one factor alone: which approach will bring the governing party the most votes in elections. Agriculture as a sector of the economy is sacrificed in favor of populist and pseudo-nationalist approaches. As a result, both the rural and the urban areas are becoming depopulated, as people leave the country. During the last 20 years, the population of Georgia fell by 1.5 million on account of emigration.