“There are three factors that have caused the spread of poverty in Georgia, the chief among them being people taking out out loans.” – Bidzina Ivanishvili.

Speaking before the first round of the presidential elections, former Prime Minister of Georgia Bidzina Ivanishvili identified loans and excessive debt as the prime reasons for the spread of poverty in the country. The second round of the elections was preceded by the announcement that Mr. Ivanishvili’s Kartu Foundation would be covering debts of up to ₾2,000 for people across all of Georgia who had been unable to repay their bank loans. The government stated that the goal of this measure was to reduce the volume of bad debt.

New regulations are due to come into effect on the Georgian financial market in 2019. More specifically, changes to lending rules for natural persons will lead to the introduction of a rigid framework for the financial sector. Lending procedures will change significantly, with an in-depth examination of a person’s ability to repay becoming mandatory.

The planned changes are aimed at reducing the volume of debt in the country. The chairman of the ruling party ascribes national poverty to the prevalence of the aforementioned loans. However, one must ask whether citizens are poor prior to taking out loans, or whether the loans make them poor. Which comes first – the loans or poverty?

There is no single methodology for assessing the level of debt. An important measuring criterion is the ratio of non-performing loans to total gross loans in the banking sector. According to IMF data, Georgia’s figure based on this criterion is one of the lowest in Europe at 2.7%. For comparison, numerous European countries have a far greater number of accounts in arrears (4.2% in Denmark, 9% in Ireland, 9.8% in Italy, 10% in Russia, 11% in Portugal).

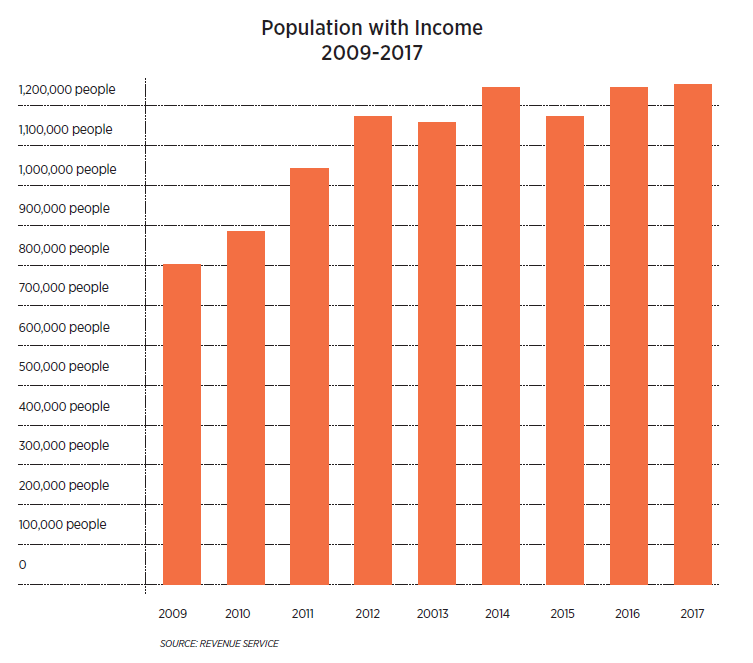

According to the 2017 National Bank of Georgia (NBG) report, one million people took out loans without having any income officially registered to their name. The report also shows that the arrears figures are particularly high in the micro-loan portfolio. NBG calculates that out of all the issued loans of up to ₾400 GEL, 45% were overdue. Two-month ₾200 loans with a 43% annual interest rate, or three-month ₾250 loans with a 46% annual interest rate, are typical micro-loans issued by the Georgian finance sector today. According to official data, the types of loans that are predominantly issued to people with the lowest income, account for the highest loan arrears figures.

According to NBG data, arrears figures for loans issued to natural persons by amount are as follows:

Loans of up to ₾400 – 45%;

Loans of ₾400-1,000 – 25%;

Loans of ₾1,000-2,500 – 23%;

Loans of ₾2,500-5,000 – 20%;

Loans of ₾5,000-10,000 – 17%;

Loans of ₾10,000-20,000 – 13%;

Loans of ₾20,000-100,000 – 8%;

Loans of over ₾100,000 – 5%;

The government’s response to the high level of arrears in category of loans up to ₾400 is to virtually prohibit the issuance of such loans without carrying out detailed background checks of the loanee’s income and property. Furthermore, the loan issuer must set an upper limit to the amount that a person with a specific income is able to repay on a monthly basis.

It is likely that this move will limit the access of a sizeable section of the population to the legal loan market. It is difficult to predict whether or not this decision will improve the situation for those who are consistently experiencing financial difficulties due to their social background.

According to the Revenue Service of the Ministry of Finance, 230,000 citizens of Georgia had a salary of less than ₾1,200 per year, or less than ₾100 per month, in 2017. The total number of people with a declared income of less than ₾400 per month exceeds 537,000.

The aforementioned section of the population finds it difficult to support themselves and their families. It is likely that the NBG’s new rules for the commercial banks and the financial sector will mean that these people will lose access to a key source of funds to supplement their seasonal and low income.

The size of the issued loans also indicates that they are mostly used as a means to resolve short-term liquidity problems. Three-month ₾200 loans or six-month ₾350 loans are needed by thousands of people with no savings to cover unexpected or urgent expenses.

The provincial regions account for the largest share of the informal sector of the economy. Up to one million persons are self-employed in agriculture. Due to the lack of sustainable income, cash shortages are particularly problematic for them.

Due to the risks associated with issuing loans to individuals without a stable income, such loans usually come with high interest rates. High risks are one of the reasons why arrears figures are so high in this section of the credit market. People on low income struggle to service their existing debts, or even worse – they are dragged into the spiral of taking on new debt, which worsens their financial situation even further.

Overdue loans also present another problem: to avoid automatic enforcement, hundreds of people are shying away from finding employment in the formal sector.

With or without debt, it is clear that a sizeable section of the Georgian population lives in poverty. Excessive debt is only one aspect of this problem.

Against the background of the ongoing public discussion on the topics, we must ask whether ‘excessive debt’ is a repackaged equivalent of poverty, and whether tackling debt, rather than poverty, can produce any results.

If excessive debt is a consequence of poverty, then it is unclear what can be achieved by fighting the effect, rather than the cause. Or what will happen when the lowest-income sections of society realize that they are unable to take out loans as a result of the new regulations?

It is politically convenient for the government to claim that these planned measures will prevent people from ruining themselves through loans. However, no studies of the socio-economic effects of these regulations have been presented.

The National Bank of Georgia admits that these regulations will have a negative effect on the economy in the short term. However, the NBG insists that the long-term results will be positive.

Georgia has one of the lowest figures of non-performing loans among the European countries, which is a key criterion for measuring the health of the financial sector.

Another indicator of market health is the so-called ‘percentage spread,’ which is calculated by subtracting the interest on bank deposits from the interest on loans issued by the bank.

The percentage spread shows that banks used to retain a higher percentage from their operations in the past than they do now. The higher the difference between the interest rates on loans and deposits, the more money is retained by the commercial bank for profit and for insuring its operations and credit risks. The lower the spread between loans and deposits, the less money is retained by the bank for its operations.

The growth/decrease of the percentage spread is also an indicator of general expectations of the banking sector. If there is high uncertainty, then the percentage spread will increase to act as a buffer in the financial sector. On the other hand, lower risks will lead to a decrease in the percentage spread.

According to NBG data, as of the fourth quarter of 2017, the average percentage difference between the loans and the deposits was only 5.1%. The percentage spread was higher in 2011 (7.2%), meaning that banks were retaining more funds for profit and operations than they do today. This indicates that unlike the National Bank, the banking sector does not perceive overdue microloans of natural persons as a fundamental risk.

Nevertheless, the government is supporting changes which will slow the country’s economic growth. Private business representatives have stated that these regulations “will endanger the process of forming a stable business environment in Georgia and reduce economic growth, which will have an equal impact upon each citizen.”

Slow economic growth will create obstacles to job creation. This, in turn, will hinder the efforts to eliminate poverty in the country.

On the other hand, excessive debt is not the only source of criticism of the financial sector by politicians. Figures of authority also lament the high interest rates and point out that expensive loans create major obstacles to the development of business in Georgia.

In reality, however, loans are much cheaper in Georgia than in other countries in the region. This is against the background of stricter monetary policies that make it virtually impossible to issue loans in national currency with interest rates below 7%. According to World Bank data, the average interest rate on loans in national currency is 11.5% in Georgia, 14.4% in Armenia,16.4% in Ukraine, 16.5% in Azerbaijan and 9.7% in Belarus.

The country’s credit risk is a key factor that determines the interest rates in the country. The credit risk is calculated by neutral international rating agencies likeMoody’s, Fitch and S&Pbased on objective criteria. Fitch assigns a BB- rating to Georgia. Although this score is higher than that of the poorest developing countries, it still falls in the junk category. A credit rating can be improved precisely through high economic growth, political stability and lower poverty levels. If that is achieved, then Georgia can come closer to attaining European interest rate values.