Electric Bagpipe! Sounds weird, right? Well, that’s exactly what Kakha Kuchava was told when he first revealed his mining plan. Finally, with just GEL 1 million, his JSC Caucasus Minerals paved the way to the exploration of mine where over GEL 500 million worth of metal antimony was buried in the ground.

It was 5:30a.m., and the alarm was blaring in my ear. Problem is, it didn’t really interrupt my sleep. A few minutes later however, the phone rang, and woke me from my dreams. I was still half asleep as I walked down Alexander Chavchavadze Street on autopilot mode. I embraced the city as if it were my long-lost-friend. So familiar, and yet still completely strange. As I walked, I noticed an SUV by the Opera Theatre. I made no effort to discern the faces of the people standing by the car, since there was no one else on the street. I knew that I was going in the right direction. He sat at the wheel and chose the musical menu for our trip.

“I would sing if I were alone,” he said cheerfully.

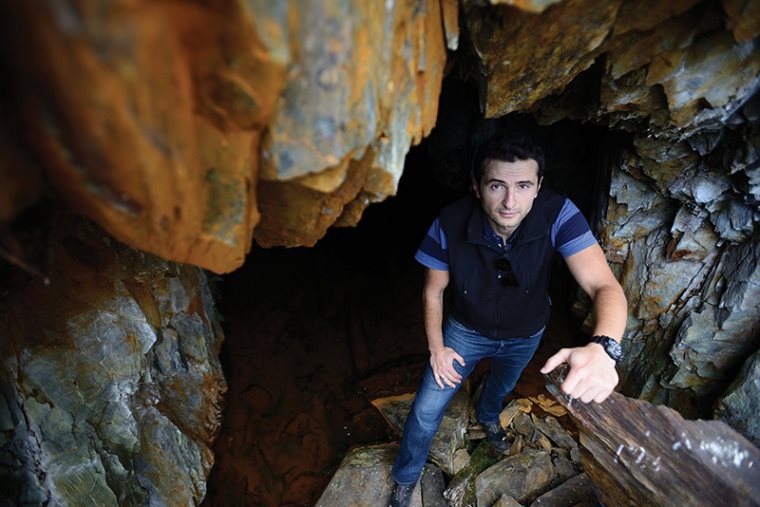

For a couple of hours Kakha Kuchava’s contagious energy assumed the role of the caffeine that was sorely lacking in my bloodstream. Then somewhere close the Zestaponi, I fell asleep. I woke up again in Oni. We changed the car. We had to drive from Oni to Ghebi and then drive 17 more kilometers off-road to the top of Ghebi – Zokhito. It’s located 1,600 meters above sea level. It takes us more than an hour to cover this distance. I do not know for sure what kept me awake, the beauty of the landscape or the car jumping like a horse. First we passed the ‘houses’ that are one and a half meters high. They’re more like hobbit houses than houses built for humans. Everyone recognizes the 36-year-old Kakha Kuchava from afar. The severe local climate is well reflected in the nature of these heavy-set, robust people. If, God forbid, they dislike you for any reason, no one will care if you are an entrepreneur or the Emperor of Manchuria. They will be humble and pitiless like a landslide. However, everyone around here demonstrated a rare warmth towards Kuchava. Those who are familiar with the highlands, know that this warmth of heart should not be taken for granted. It is rare, but is in line with the laws of nature. That is why it’s valued so much.

The reason for my long trip is a 5th period, group 15 chemical element with an atomic number of 51, according to Dimitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table. In other words, antimony – also known as stibium and surma. I have no intent on offending geologists, but the real reason for my long trip was Kuchava’s persistence and determination. One of the best Georgian specialists in corporate lawand far from the profession of a geologist, Kuchava saw a chance and started a business that will potentially give his company Caucasus Minerals an opportunity to mine 30,000 tons of antimony. Today the market price per ton of antimony is $8,000.However, according to the forecasts, the price is expected to double in ten years. Consequently, the market price for that amount of antimony is at least $240 million. Needless to say, Kuchava’s income from his mining business will not be equivalent to the market price of antimony. Moreover, he will most likely sell the ore (estimated market value $5,500 – $6,000 per ton) and not the refined metal. As you well know, profit is the surplus remaining after capital and operating costs are deducted from total revenue. But for the Racha-Lechkhumi and KvemoSvaneti region, where, according to 2013 records, the industry production output did not exceed GEL 6,800,000, this is more than just another business. This is more than a ‘crazy’ idea. This is a business that started with GEL 1,000,000 in foreign investment and a few tents.

The road that we took was built by Caucasus Minerals. A major part of this 18 km road is used by the local villagers, the last 6 km is used mostly by the company. The company also built a bridge over the Rioni River. Prior to that, it was impossible to cross the river because of the strong current. After the Rioni, there is another bridge over the Zohkhitura River.

“Don’t be misled by the wooden cover, there is stone and iron underneath it. This bridge can withstand a four ton vehicle,” noted Kuchava, the founding partner and director of Caucasus Minerals. This bridge is also his creation, and he has a reason to be proud of it. However, he is more proud of his employees. We continue our journey on foot. On our way to the base I listen to stories about ‘honest Mamuka’, ‘gifted Lebo’ and one about a kickboxing champion from Ghebi, who tells Kakha in English – ‘call me’ and then laughs at his own words.

Caucasus Minerals has a camp with cottages that can house 22 people. There are approximately 30 employees that have been working for Caucasus Minerals since 2012. All of the employees are locals, except for the Tbilisi office staff.

“First we came here with small tents, then we used larger military tents and now we have cottages,” Kuchava explains to me, as he fills me in on their annual progress while pointing to the landscape in front of us. Caucasus Minerals possesses a 30-year license for the exploration and mining of antimony. The first five years will be completely dedicated to exploration, and when the company moves to the test production stage, the number of employees will increase to up to 70 people. When the company starts full-scale mining operations, the number of employees will then increase to 300 people.

The nearby cottages are springing-up like mushrooms after the rain. At the present moment there are only 350 families residing in Ghrebi, which was once a densely populated village (the gigantic size of the local secondary school is testimony to this). A long-term work plan means a lot for this area – one of the poorest regions in Georgia – particularly in view of the fact that the wages for miners are now up to GEL 1,200.

We continue on our way. The antimony deposit is one kilometer away from the base. I am already exhausted, but we still have to walk another 40 minutes to the deposit. “How often do you have to travel here from Tbilisi?”I ask Kuchava, expecting him to tell me that it’s a ‘quarterly’ occurrence.

“Sometimes I travel here three times a week. There is plenty of work here,” Kuchava replies, as he continues to walk energetically towards the deposit 2,400 meters above sea level. On the other side of the deposit lies the Russian Federation. Clearly, he is one of the commanders that lead his subordinates to the ‘front line’. That’s what makes a real leader different from a boss. The locals of Ghrebi like their work leader. Being bossy here is unheard of. The mountains have no boss.

Kuchava’s work experience is more extensive than the playlist in his car. In 2001, still a student at the law faculty, Kuchava was already working for the International Legal Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Later, he started a private legal practice and went on to continue his studies in the UK. He worked for the Georgian Red Cross Society, then GEPLAC – an EU-funded project that promotes the political, economic and social convergence of Georgia and the European Union. After that, he worked for USAID.

“I had the greatest boss when I worked for the USAID. He was an American named McGill. He gave us complete freedom, and told us to use our imagination,” Kuchava fondly recalls. This freedom of imagination contributed to the reforms in the public registry, tying the tax base directly to the registry and lessening the bureaucracy. Later on, he started working at the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and became a corporate management specialist.

“It was the beginning of a new life. The IFC is an organization that spends a lot of its resources on making you a better specialist,” Kuchava told me. He had no trouble mastering his trade and becoming an even better professional. In a year and a half he was already responsible for the regions spanning from Central Eastern Europe to Central Eastern Asia – essentially from the Balkan Peninsula to Mongolia. He worked at the IFC from 2007 to 2010.

“I was in the air all the time,” he recalls cheerfully. “I always had the ambition to create something of my own. I did not want to be a lawyer for some organization that would eventually end up in Washington.”

That was how the Eristavi & Partners Law Firm was founded, together with David Eristavi and Rezo Beridze. Along with his partners, Kuchava demonstrated his top-notch skills in his private business. The law firm was business oriented from the very outset. In the midst of the 2009 economic crisis, the law firm devised a very innovative solution. In exchange for their legal services, Eristavi & Partners asked companies, which were on the brink of bankruptcy, for a share in their business. Eristavi & Partners helped companies rise from the ashes. Consequently, the company took on valuable assets that belonged to successful businesses, and the firm established a good working relationship with several banks. Eristavi & Partners never let the banks down, always holding up their end of the deal. In certain cases, if the company that was in the difficult situation happened to be a state contractor, Eristavi & Partners received their sincere gratitude. As a result of a couple of successful projects, Eristavi & Partners now owns a 9story 130room apartment/hotel in Gudauri, right behind the ski lifts. The hotel is expected to open soon.

Eristavi & Partners came up with an innovative billing practice –a monthly salary, rather than an hourly payment. This move enabled the firm to plan its budget in advance. For a time, Eristavi & Partners was the largest law firm based on its number of employees

From the very outset, the company strived for greater diversification. That’s when Kuchava remembered the mine that his Australian client was interested in about ten years back. In 2004, the Australians abandoned the excavation site and Zopkhito was left unattended.

“In 2010 I made some inquiries, and found that the mine was still free. There were two companies before us that failed to bring the mine into operation and therefore the state confiscated the mine from the companies. According to a law issued in 2005, the exploration period can last for five years. Since the company hadn’t fulfilled any significant work in that period, the mine was again on the market,” noted Kuchava.

That’s when Kuchava decided to go into the mining business and began studying geology. It was at that point that many viewed Kuchava as slightly crazy for suddenly dedicating his life to geology and a 32-hour commute every week, just to start a business that had been a failure since 1930. Even some of his partners at his own legal firm emphasized that this whole idea was nothing but madness. Eventually they came around to trusting their friend. Dato Eristavi took over the construction field at Eristavi & Partners, Rezo Beridze focused on the law firm itself, and Kuchava ended-up surrounding himself in the vast nature of the alpine zone.

In going forward with his new risky endeavor, Kuchava sorted out all the paperwork with his usual diligence, shared information with several organizations, and received a prompt response. Martin Churchouse invited him to London to discuss the project. The meeting lasted about 15 minutes. This is exactly how long it took Kuchava to convince his future partner to give him a million lari. There are no records as to what exactly Kuchava said or did at the London meeting. However, the ink on the contract he signed had hardly dried and Kuchava has already received a 1 million GEL transfer. It would be hard to find another example that demonstrates such trust. Kuchava made the required GEL 990,000 advance payment in order to participate in the auction. Eventually they won.

“Come to think of it, it was definitely a very adventurous and risky start,” Kuchava admits. “I should not have worried so much though. The obligations and demands were very high and lots of companies were simply too scared to participate,” he told me.

As it turned out, the mine was so well explored by Soviet geologists that it completely coincided with Wardell Armstrong’s data. The current price for the work conducted between 1930 and 1980 would be approximately $45-60 million today. There were tunnels that spanned 27 km, along with eight volumes of research data (3,000 pages total), 11,000 samples and detailed archaeological maps – these were the historical records that came with the mine. After taking the data to the JORC and synchronizing them with independent analyses, it produced a very attractive picture: only 17 out of the total 60 veins have been examined. According to the Kernow Geological Consulting report prepared in 2012, the Zopkhito deposit may contain more than 125,000 tons of antimony. In order to fully understand the scale of this deposit, it is important that we take a look at this metalloid and its global resources.

Forget about the gold!

Gold, silver and bronze are overused. Antimony is the rising star of the mining underground. Based on the scale of the antimony resources found in the Zopkhito deposit where gold is simply a byproduct, Georgia comes in at fifth place in the world. Due to its deficiency, this silvery, lustrous gray metalloid is gradually flashing more brightly on investor radars. According to USGS estimates, the world reserve of this metalloid is only 1.83 million tons. China is the largest producer of antimony and its compounds. It has approximately 950,000 tons of this metalloid. Russia has the second largest reserve at 350,000; Bolivia: 310,000; Tajikistan 50,000, and South Africa has 21,000. With 30,000 tons of the metalloid found in 17 explored veins out of the total 60 veins, Georgia is already ahead of South Africa.

“We need to do further research, and for this we have five more years in compliance with the law before we start the production,” Kuchava says.

However, even China does not have it in the bag. Their production scale is decreasing and this presents new opportunities for foreign companies and non-Chinese investors. In China, 17% of their antimony deposits come from small, illegal and environmentally harmful mines. The Chinese government is waging a war against such mines. As a result, the export of antimony from China has significantly decreased. Along with various prohibitions and restrictions, the Chinese government is implementing other measures to reduce its share of antimony production on the global market. The People’s Republic of China is saving antimony resources for its own industrialization. However, these resources are growing smaller by the year.

As a result, the price for antimony has increased several times since 2002. Hence, the exploration of antimony in Georgia has become a very profitable business. In the beginning of the 21st century, the market price for a ton of antimony was $2,000. By 2011, the price had reached almost $15,000. Although the price has almost halved since then, experts predict a 5% annual increase, and by 2020, the price per ton of antimony is expected to reach $20,000 – that is exactly when Kuchava will move to full-scale production.

Kuchava has not let his dreams curb his skepticism. He has both feet on the ground when it comes to pursuing this endeavor, a ground that is rich with ore. “The price may go down, or they may come up with a substitute material that will reduce the price of antimony or find a new deposit that will increase the existing supply,” says Kuchava.

“I came upon some very optimistic expectation for the Racha region when I tried to search for materials regarding any possible threats to Caucasus Minerals. I think that the price for antimony will increase,” explained Christopher Ecclestone, Principal Analyst and Mining Strategist at Hallgarten &Company. His assumption is backed by official documents. In a 2012 report, this metalloid was declared a critical raw material for the European Union. According to the Roskill’s Antimony Report, China will not increase the production of this metalloid in the near future. According to USGS statistics, the current resources will run out in 13 years (although it is possible that new supplies will be found). The British Geological Survey put antimony on its risk list. This list includes chemical elements or groups of chemical elements that run a high risk of becoming designated a supply shortage. These are elements that are necessary to maintain the contemporary British economy and lifestyle.

The application of this substance is narrow, but at the same time, widely common – 60% is used for making fire retardants, and 20% of antimony alloys are used for making batteries and screens. Recently, they started using antimony in memory chips, which has dramatically increased the speed of information exchange.

Antimony is a substance with no substitute, and one that has deep roots in the contemporary consumer goods economy. The need for fire retardants will be there as long as the candle of humanity is burning. Therefore, in light of all this, and the fact that the global supply of antimony is running short, the only logical assumption is that the price for antimony will only increase.

Caucasus Minerals is in no hurry

When the mining sector crisis began, the partners bought 50% of the shares back from the Brits. Shortly after, Georgian banker Nikoloz Enukidze demonstrated interest in the project and bought 27% of the company’s shares. 70% of the shares remain in the hands of Kuchava, Beridze and Eristavi. Three other people own a 1% minority interest.

“We made a decision to make this project all Georgian till the end. Such projects require patriotism. In any case, we care more about the people living the Georgian villages than foreigners do,” Kuchava explains.

That is probably the reason why the company decided not to build an ore-processing plant, which would inevitably pollute the environment. Instead, they decided to resort to a relatively more expensive method of manually processing the ore. Consequently, Caucasus Minerals will sell ore with a 50-55% concentration and produce approximately 4,000 every year. This means that more people will be employed at the company.

The company has been spending approximately $1 million every year since the issuance of the license in 2012. Next year, Caucasus Minerals plans to start test production that will bring their operating costs up to $15 million. According to the current estimates, another $4 million will be spent during the remaining exploration period. However, this amount may reach $15 million.“The costs will increase if we see results coming from the exploration,” says Kuchava.

Test production means that the ore will be mined from one point in order to determine what should be expected in the case of large-scale mining. A financial model can be specified only after the percentage of the extracted ore is determined. By that time, the company will know what sort of machinery they will require, the estimated costs, time-frame, safety measures and mining techniques. Since the concentration of antimony in the ore is very high, there is a high probability that the technological process will be easy, and there will be no need for building an ore-processing plant.

After the exploration, the company will be able to determine the costs for mining the byproduct – gold. Individual content in samples is as high as 11 grams per ton. “We need to make some calculations in order to determine whether we should focus on gold, and whether or not it will cover its mining costs,” says Kuchava. “Gold can be a headache for someone who is producing antimony. However, the content of gold in the ore is very interesting. The extraction percentage that we have is very high. Anything over 80% is considered good and we have 94%,” he adds.

It is hard to predict what the future holds for Rachan antimony before the launch of the test production. However, we can be certain that it is in good hands. The company has demonstrated exemplary corporate responsibility both from the ecological point of view and with regard to labor ethics. The workforce is exclusively local. The company uses only local products and buys gasoline in Oni. This is more expensive than buying it in Tbilisi and transporting it to the mine, but it is absolutely necessary to do so.

Three years after its start of operations, Caucasus Minerals has become the second company in Georgia to have constructed a 3D model of the mine, and it is very likely that it will also be the first company to move from the so-called ‘greenfield’ level to the production stage. “I love challenges. Challenges and difficulties are there to be overcome. If I start something, I know that I will see it through to the end. I said the same about this project. I said we would be the first mine in Georgia that starts a project from scratch and moves to production. We are also very proud that this project will be implemented in full compliance with JORC standards,” Kuchava notes.