The emerging multipolar world offers a large and attractive infrastructure opportunity, financing, building and operating critical public works around the world in a $3 trillion annual marketplace. The path to progress around the world runs through infrastructure (and its twin, education), in areas ranging from clean air and water, to efficient trade, communications and transport, and now to digitization, big data, robotics and advanced manufacturing. The geo-strategic character of this marketplace is increasingly powerful, while mightily misunderstood – particularly in the U.S.. This is dangerous, presenting threats as well as opportunities, in a global marketplace in which the U.S. is increasingly absent.

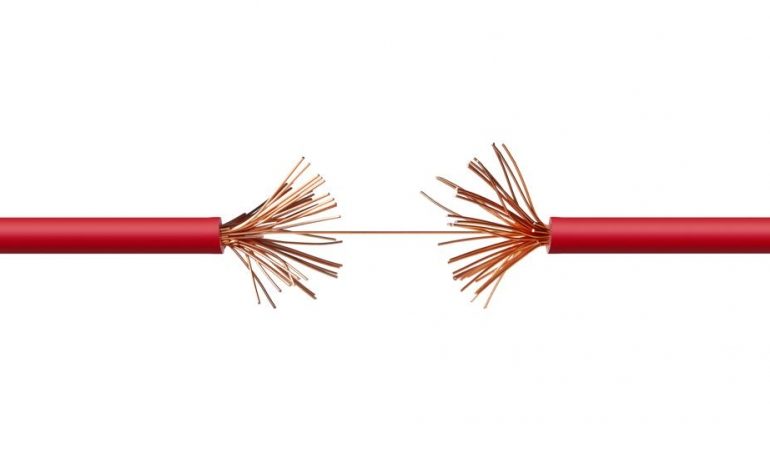

The Market Fault Line. The U.S. tends to see overseas markets as purely commercial opportunities, a space reserved for top notch private sector executives; China sees infrastructure projects as existing within public space, and therefore as state opportunities, the clear province of public power; Europeans often split the difference, seeing international public works as somewhere in the wild middle, hence their creation and wide embrace of the public-private partnership model. Each of these views is a natural reflection of the way local markets developed and currently operate. In the global marketplace of the 2020’s success tends to have a public face.

This is important because the prize for winning is enormous, and enormously strategic, including: banking goodwill of citizens around the world; conquering robust business opportunities; and gaining rich, highly leverage-able, geo-strategic influence. What is more concerning than the retreat of the U.S. and of U.S. companies from this critical market is that we – public and private sector alike – seem to completely misunderstand the nature of the game. It is not a buying and selling – I win and you lose – market, rather it is deeply strategic. Winning places the victors in a dominant geographic position, with a very high moat, for a very long time.

One fact makes this point: The value we ascribe to the $3 trillion global marketplace vastly undershoots the strategic value, based as it is on our own short-sighted commercial logic; the strategic value is in fact $21-$30 trillion each year for the next 30-40 years. The size of each project’s O&M aftermarket traces the projects real value, and that is 7-10 times the original capital cost of a project. Winning a contract today is ownership of that contract – and that geographic footprint – through to 2050 – 2060.

Infrastructure and GeoStrategy. National borders are relatively fixed, a signal achievement of the post-war Bretton Woods agreement; infrastructure competition, on the other hand, has created the equivalent of a global land grab that is not just unsettling, but profoundly disruptive – and a direct threat to the health of economies in the U.S., the West and in emerging markets. As George Friedman wrote – in dramatic understatement – describing the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis, ‘what is most interesting is the absence of the U.S.’ Substitute “interesting” for “shocking.” In this new geo-strategic infrastructure game the U.S. – around the world – is no longer on the board, and you can not underestimate the signal importance of that fact.

This business and influence grab is playing out most intensely – and dangerously – across the Eurasian land mass. It is also profoundly disrupting all of the key economies of Latin America and Africa. The press highlights China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative as dominating the region, but there are three competing forces – and three powerful models – that are influential, and at least two of the three are profoundly anti-market, and anti country stakeholder.

OBOR is well-known, gets all the press, and is designed and financed by the Chinese government in Beijing. OBOR Eurasian investment is estimated at a cumulative $1 trillion – using our 7X rule of thumb, China has a current aftermarket in the region of as much as $7 trillion, through 2050! This is a major strategic advantage, especially given that these projects are driven by decisions made thousands of miles away, utilize only token amounts of local labor, and spend little on capacitating local expertise. The Chinese model, with more than 50% of funding coming from Chinese public sources in Beijing, has weaknesses – large public debt, shallow local support – and at the same time that it goes forth in a vacuum of alternatives, creates enormous strategic benefits for Beijing.

The Asianization of Asia model, popularized by Parag Khanna, sees Asian nations – from Japan to Indonesia and on to India – coming together driven by their internal strategies, savings and vision, and fueled to a significant extent by the catalytic financial assistance of Japan. A recent Bloomberg report highlighted Japan’s dominance – funding $367 billion in projects in Asia’s six largest economies, as against Chinese investment of $255 billion. In this narrative the Japanese foreign assistance model drives market growth, along with predictable and robust opportunities for Japanese firms.

A third model is the traditional one that exists in our mind’s eye, playing out mostly on Russia’s near abroad, as Russia battles to maintain influence over the satellites of the former Soviet Union, including Kazakstan, Azerbaijan and Georgia. A big part of this story is energy but – increasingly – data and the value of that data, the energy of the 21st century, are creating significant tension. This is a narrative that is more 20th than 21st century, using brute power to drive strategic advantage, especially including control over energy resources.

The Complete Absence of the U.S. It is important to drive home the point, because it is so incredible, that the U.S., public and private, is essentially absent. There are no U.S. firms among the Top 20 global contractors (ENR’s annual 2020 list): 11 are Chinese firms, 7 are European, and 2 are Japanese. The largest firm on the list is China State Construction Engineering Corporation (SHA), with $230 billion in annual revenue; the largest European firm, coming in at #6 is France’s Vinci, with $48 billion in annual revenue; and the largest Japanese firm, at #15, is Obayashi (OBYCF), with $17 billion in annual revenue.

A Tale of Two Projects. The big takeaway is that in the emerging global infrastructure competition both the independence of smaller nations and the idea of free markets are under threat. Two projects perhaps highlight this fact:

The Digital Silk Way project connects Kazakhstan by fiberoptic cable with Europe, traversing the Caspian, passing through Azerbaijan and Georgia, and passing underneath the Black Sea. Data centers will be established in both Georgia and Azerbaijan. Russia, whose network is being bypassed, sees the project as a threat to its data control of the region, and so is putting enormous pressure on Georgia to void the legal sale of the Georgian cable operator’s assets to Neqsol Holding, the project’s Azerbaijani developer. No one is filling the role of the U.S. and standing with Georgia, or with the principle of property rights, on this transformative project that would provide high speed internet to as many as 1.8 billion people.

In Myanmar a similar operation is unfolding, one which is being repeated throughout Southeast Asian. A local entrepreneur is interested in developing a multimodal port project to enable trade from Southeast Asia’s former breadbasket, the Irrawaddy rice growing region, to India and other global markets through the Bay of Bengal. This multibillion dollar project is opposed by China, and – as with Russia in Georgia – enormous pressure is being placed on local politicians as a way of interrupting the project – with no countervailing encouragement to private enterprise, market forces or a vision of a strong and independent Myanmar.

A More Effective Geo-strategy. Infrastructure, which in the past was simply public works, is profoundly strategic – it is where the Great Game is now played. This is a $21 trillion global market, with a long tail reaching deep into the future. The way the world creates public goods for citizens around the world needs a complete redesign, particularly as we try to recover from Covid-19 – and create a stable world for humanity’s children and grandchildren.

As a starting point, three ideas come to mind. First, the entire infrastructure business needs to be recast in a way that a) puts everyone on a level playing field, and b) is focused on empowering countries, local markets, and the voice of citizens.

Second, the West needs to create an effective funding strategy – you can’t compete with something you don’t like without real tools, sustained over time. As a Chinese executive told me, “if you don’t like what we are doing that’s fine, what are you offering as a replacement?” Remember, today’s project is still your market in 2050! By providing funding that leverages local resources – capital, and especially local engineering capacity – the center of decision-making will become increasingly competent, and increasingly local.

Third, the private sector’s ‘go it alone’ model has not only failed, but actively masked strategic weakness – to the extent that we don’t recognize the severity of the problem, and so are not focusing on solutions that achieve our objectives. It is vitally important to begin to see infrastructure strategically, rather than commercially.

Charles Dickens, writing about the French Revolution, gets the last word: “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epic of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness….” Its time to once again bring the light.

"Forbes Georgia-ის სარედაქციო ბლოგპოსტების სერია "როგორ გამდიდრდა“ და "საქართველო რეიტინგებში".